Dave Waters, Paetoro Consulting UK Ltd

Scope 1&2 Hydrocarbon Greenhouse Gas (GHG) emmisions

(Related to fuel combustion and fugitive emmisions and in the energy used for production)

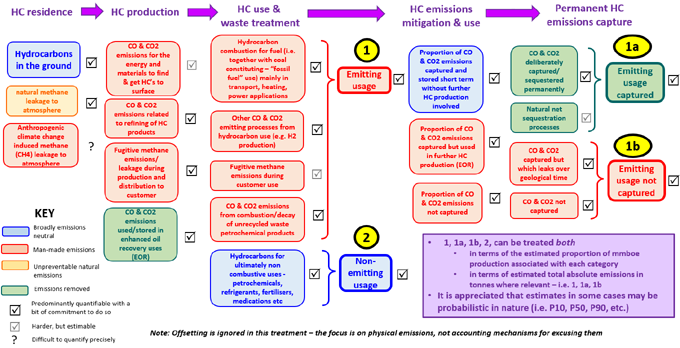

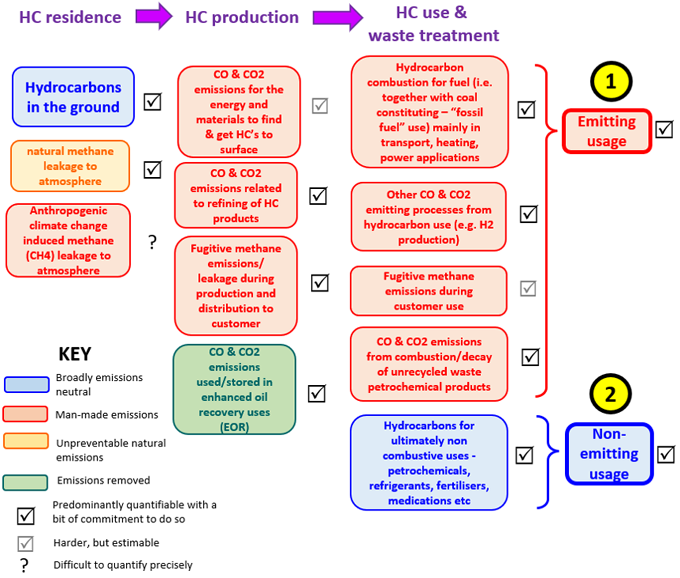

Hydrocarbons are not just fossil fuels. They have other uses. This is something I’ve treated in more detail previously.

The fossil fuel use is the most controversial as it produces greenhouse gas (GHG) carbon (CO and CO2) emissions. Some other processes, including some methods of hydrogen production, also involve emissions. Fossil fuel usage is a characteristic of transport, heating, cooling, and power applications – residential, commercial, industrially. Note that fossil fuels still form a huge proportion of the world’s primary energy use (about 80%). That is not to be confused with power production, where renewables are making greater inroads. Power is only a fraction of a country’s total primary energy use – for somewhere like UK, something like 20%. That is changing slowly as electrification of various energy uses takes hold.

Primary energy use is also not the whole story, as it fails to take account of energy efficiencies, the total energy delivered, and combustion is inherently inefficient – much energy is wasted as dissipated heat. Electrical uses can be several times more efficient, which means that electrification does not have to replace all the primary energy usage currently allocated to hydrocarbons, just a fraction of it. You need less primary energy to do stuff with electricity than you do combustion.

Nevertheless, currently, roughly 10% of global hydrocarbon use is not for emitting fossil fuel but for other uses, which the world will continue to need and which do not directly impact to anthropogenic global climate change fears.

The hydrocarbon industry rightly makes this point, as a reason for ongoing global hydrocarbon demand. For oil it is usually about 10-15% of production and includes things like, lubricants, refrigerants for cooling, chemical catalysts in industry, plastics, asphalt for roads, roofing and pavements, medicines, and paints. For gas it is less than 5% usually, and includes fertilisers and other chemical products – although it is worth noting that some of these processes – for example the production of hydrogen – are also themselves emitting of CO of CO2. They are however often vital for global food production.

Be careful what you wish for

It is a fair cop for the hydrocarbon industry to say this to us. These needs are not going to go away. Shutting down production of fertiliser and plastics is not advisable. Yes single use plastics are being progressively shut down, but an awful lot of what we do day to day involves multiple use recyclable plastics. We continue to need those almost ubiquitously in modern society.

As a general rule though, burning hydrocarbons is a bit mad given they are so useful and a ultimately finite resource. Even anthropogenic climate change concerns aside, there is an argument for preserving them, for use by long term posterity. That’s something for another day.

Meanwhile though, let’s accept the hydrocarbon industry argument that some ongoing global non-emitting hydrocarbon needs will continue a need for production. Having made that argument, the hydrocarbon industry can’t have it’s cake and eat it. If that is a key argument (not the only one, but a key one) then an account of what their emitting and non-emitting hydrocarbon production proportion is, needs to be provided.

But it’s too hard? No it’s not. Hard, yes, too hard, no

Immediately I can subconsciously hear the protestations – about how this isn’t easy. After all it is the refining companies, not producers, that ultimately delver to various customers, and those customers may change month on month, week by week, day on day. Yet if defies logic that it is not estimable with a bit of effort and communication. Given the technological and scientific obstacles this industry routinely faces – to estimate their own production’s applications is not beyond them. Is there time and cost involved in doing so? Yes.

Let’s remind ourselves what is at stake here though. Anthropogenic climate change, and investor confidence. If the protestation is that this is hard to do, then the appropriate response is , well, better get started on it now then. If the argument is that we need to keep investing in hydrocarbons to provide all those non-emitting uses we employ them for daily, then this is the tool to facilitate it. It provides investors with the metrics to see who is devoting most of their hydrocarbon production to that use.

Admitting the emitting and cutting some slack

Although I can’t know for sure, the actual reason companies are reluctant to so this, more likely, is that as we have already seen the proportion of production devoted to non-emitting use is actually quite small – in the 10-20% bracket. Admitting to that publicly is a tough call.

This is where a bit of pragmatism on the part of to world is required. We need to say to the industry – look, OK, we get it – we need some of these products indefinitely, so we can’t shut you down, and we also get that for now, non-emitting uses are a relatively small proportion of the total. What we want from you though, is an indication from yourself of a sustained trend away from emitting uses, even if you start small. To do that we need to see a regularly published auditable account of what that number is for your company.

Meanwhile, there are other discussions to be had on the emitting uses of hydrocarbons, such as the use of gas or power in otherwise energy poor emerging economies, but that is a separate issue for another day.

Watch out for the accounting cloaks

I hesitate to use the word “tricks” – but there are other things to be aware of here too, in expecting such accounting to take place:

- For starters, ignore offsetting which is a whole minefield on its own. We are interested initially in the physical emissions. Any offsetting hullaballoo discussion can come later.

- Any account of greenhouse gas emissions needs to treat both carbon emissions and methane, including those that are accidental due to leakage.

- An account needs to include emissions that are not related to combustion – such as in the production of hydrogen or other chemical feedstocks.

- While petrochemical uses are not themselves emitting, if at the end of their life they are burnt without recycling that also needs to be considered.

Capturing the capturing

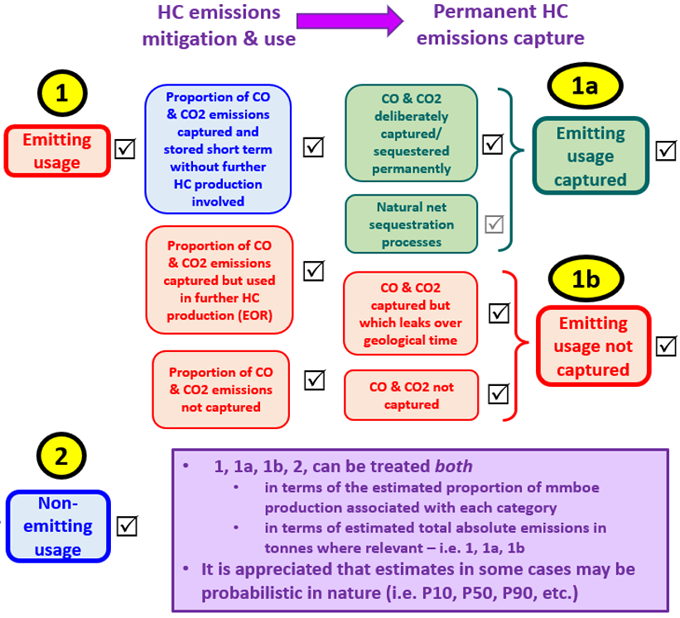

The other key aspect coming more and more into view is carbon capture, and if companies have gone to the effort of accounting for their emitting and non-emitting production proportions, it is a relatively easy step for them to then tell us what percentage of that emitting usage is being mitigated by carbon capture. Not to belittle how difficult it is too, but it is probably somewhat easier than the emitting/non-emitting usage accounting.

The need though, of course, is to be quantitative. A tack of “We are doing capture so leave us alone” won’t convince anyone anymore. So, from the emitting proportion of their production, we want to know what percentage is ultimately captured, and what percentage is not. This metric can be thought of both in terms of the proportion of production heading those routes, with units of mmboe, or in terms of absolute emissions, in tonnes. Yet again, there are certain things, certain “details” that have to be resolved out to avoid a falsely positive picture being presented. This includes:

- Any capture that is related to further enhanced oil recovery should be discounted as this leads ultimate to a net increase in emissions once all the hydrocarbon is produced. Only capture processes that do not lead to further hydrocarbon combustion emissions should be included in true “capture”.

- Any discussion of amounts of CO2 captured in the short term, by whatever route, has to be accompanied by the much more important figure of what is not captured.

- The figure of what is captured in the short term has to be accompanied by an auditable estimate of what might leak on a geological time scale. This is hard and will be probabilistic in nature but needs to be treated. If the response is that this is too hard, then the reply is that - well until we can do this, we shouldn’t be doing it. It solves little if the burial is temporary. Be it temporary on a five year or five-hundred-year time scale.

Actually, reasonable estimates can be made, and non-trivial amounts of capture are likely to be permanent. These companies have been doing geology for a long time and know the drill. They are not afraid of uncertainty or quantitative estimation in the face of uncertainty. It can be done. Again the likely reason for hesitancy to go this route is more likely that they already have an idea of what the answers are. The quantitative proportions actually being captured right now are miniscule in relation to those that aren’t.

Again the world has to be pragmatic here. CCS may never be the panacea it is currently made out to be, but if production companies are themselves up for the cost of it, and if in locally suitable areas it can sink another 5-10% or more for us as we figure out better ways to do things, then it is worthwhile. But we need to count.

If the industry is pointing at this as a mitigating reason for ongoing production, then again, it can’t have the cake and eat it. An account of how much of the produced emissions is NOT being captured in this way, as well as how much is, needs to be provided in accompaniment.

The natural stuff

It’s also worth stressing that there are some natural processes which both help and hinder.

Natural fixing of hydrocarbons occurs to some degree, but the most useful types typically occur on long time scales. This includes the oceanic dissolution of CO2 and limestone production, or weathering and alteration of surface lithologies. Some of these have adverse side effects of their own such as oceanic acidification and all the implications that has for marine life food chains including our own. Plant photosynthesis of course does this too, on shorter time scales, but depends on increased amounts of it. None of these processes are sufficient to deal with man-induced hydrocarbon related emissions on their own.

It is also worth mentioning the natural methane emissions occur. This has always happened and is essentially unpreventable. Satellite based techniques mean we can monitor these types of things better than ever before. Some of these are purely natural, others may well be triggered by anthropogenic climate change – such as effects on continental shelf hydrates, or permafrost. Those are much harder numbers to pin down – especially discerning what is due to natural versus anthropogenic climate change, but that is for our purposes an academic question and presents no obstacle to hydrocarbon production companies looking at their own numbers.

Good for the goose, good for the gander

It is worth stressing at this point if we are going to look at scope 1&2 emissions for this for hydrocarbon companies, it is not unreasonable for them to say that they should not be the only ones. Agriculture for example, generates a large amount of methane emissions. All of us should be accountable for our emissions. Not just the hydrocarbon industry. That’s not to ignore the size of the contribution they make though. They are undeniably a big ticket item on the emissions reduction hit-list.

The punchline

To me the upshot of all this is that we, and by we, I mean a society utilising hydrocarbon production companies, can go through a process of analysing sector and individual company emissions to deliver four key numbers.

First the proportion of hydrocarbon production that is dedicated to non-greenhouse gas emitting usage, and second the proportion that is. Of the latter emitting usage, we can subdivide into two further numbers – that which is captured long term, and that which isn’t. Theses metrics can be expressed as unitless proportions of oil or gas equivalent volume production, or if they involve emissions figures, in absolute tonnes of emissions. These metrics need to incorporate and consider all the caveats mentioned, and I’m sure there are others I haven’t thought of.

The problem to hydrocarbon production companies initially is that they will highlight just what a small proportion of hydrocarbon production is dedicated to non-emitting uses, and what a small proportion is currently captured. However, such accounting is necessary to convince an emissions conscious world that they are serious about emissions reductions, with the non-emitting use of hydrocarbons of long term use is an argument for ongoing production which they invoke.

The public, in response, needs to be a bit pragmatic in understanding that there is indeed a need for ongoing long term hydrocarbon production, and that if companies release theses metrics, initially they will pain a fairly grim picture. However any serious drive to improve those numbers needs their publication. Any serious commitment by companies to releasing those numbers by companies needs to involve their own increased confidence they won’t be asked to shut down the moment they do so. That will take some education of both public and politicians.

This is my effort to make sure I can’t be blamed for not trying

Scope 1&2 Hydrocarbon Greenhouse Gas (GHG) emmisions

(Related to fuel combustion and fugitive emmisions and in the energy used for production)

KeyFacts Energy Industry Directory: Paetoro Consulting

KEYFACT Energy

KEYFACT Energy