By Kathryn Porter, Watt-Logic

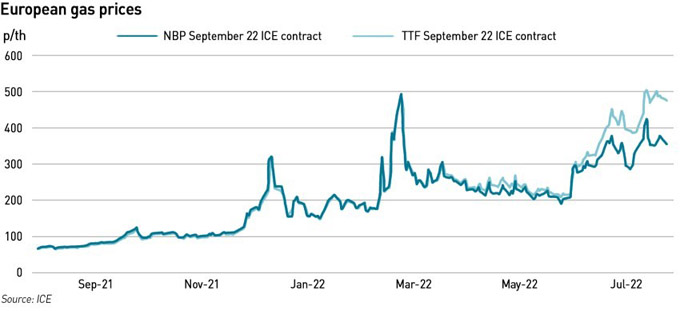

European gas prices have risen sharply in the past two months, as EU nations strive to fill gas storage facilities ahead of the winter. The widening spread between the main EU benchmark, TTF, and the British price, NBP, reflects the lack of storage in Britain which means that the market can only absorb what it needs. As a result of its summer surplus, Britain has been exporting record volumes of gas to the Continent, and National Grid has in fact requested permission from the Joint Office of Gas Transporters to increase the pipeline pressure to allow even higher amounts of gas to be sent into EU storage facilities over the summer. However, this spread will narrow in winter when British gas demand rises and the surplus evaporates.

High levels of LNG supplies unlikely to continue into the Autumn as Asian demand rebounds

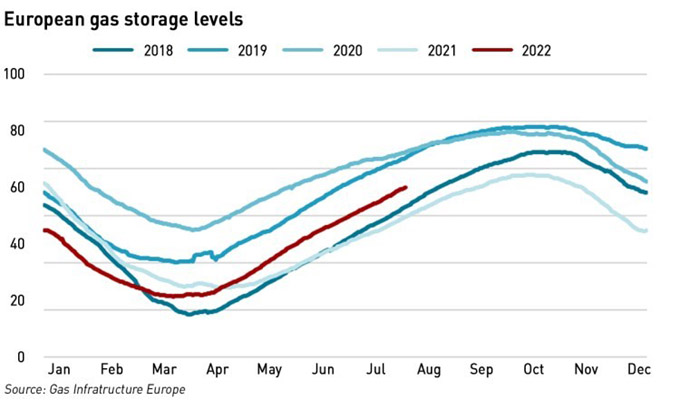

There continue to be concerns that EU gas storage targets may be missed going into the winter, despite LNG deliveries from the US to the EU looking set to exceed President Biden’s promise of an additional 15 bcm of gas.

The rate of US exports is likely to slow following a fire at Freeport LNG, which provides around 20% of the USA’s LNG processing capacity. A 700-foot section of pipe where LNG had become trapped exploded, releasing a cloud of gas that ignited in a fireball that lasted for 5 – 7 seconds, leaving a fire which burned for 30 minutes.

No injuries were reported from the explosion and fire, which consumed an estimated 1.6 million cubic feet of gas. Partial operations are not expected to resume until October at the earliest, with full operation not initially anticipated until the end of the year, however in an update last week the company said it expected to reach close to full operation in October, bringing much needed positive news to the market.

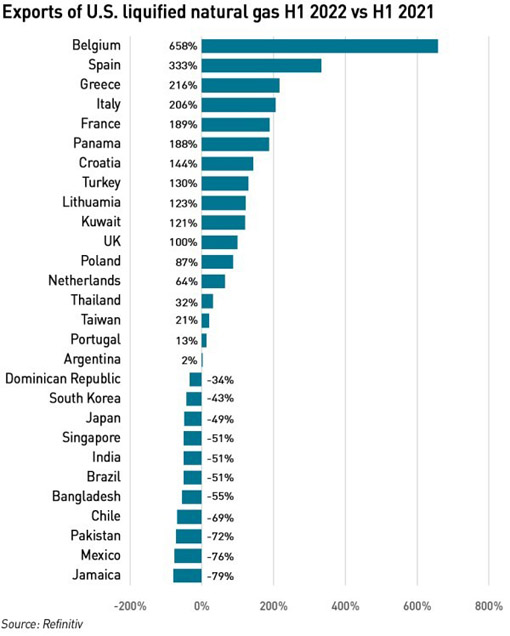

Buyers in Europe have managed to attract US LNG cargoes away from the Asian markets so far this year, driven by a need to build inventories, but with worries over Russian supplies falling further, Asian buyers are ramping up efforts to secure gas, hoping to secure winter shipments before a possible price spike.

Spot prices for gas in Europe and Asia are already trading at all-time highs for the time of year, with the Asian price discount to Europe shrinking in the last couple of weeks as utilities in Asia pay more to attract supply. This dynamic could be intensified should a covid-recovery in China result in an uptick in economic activity in the country which has yet to emerge from damaging covid-lockdowns. Either way, the global LNG market is expected to tighten again though as we move into the winter.

Worries have been expressed over the UK’s ability to attract gas this winter. Around 22% of Britain’s gas supplies are from LNG, and the country’s lack of storage means a just-in-time approach to procurement is taken. However, these concerns may be over-blown: Britain does not need to buy all of the available LNG in the global market, just enough for its needs, and as a relatively rich country, it has the ability to outbid many traditional LNG buyers. Prices, however, will be high.

“The really brutal and harsh reality is that Europe is pricing out large parts of the emerging markets. In the long term, this is not sustainable and it’s already causing energy shortages in south Asia,”

– Henning Gloystein, director of energy and climate at the Eurasia Group

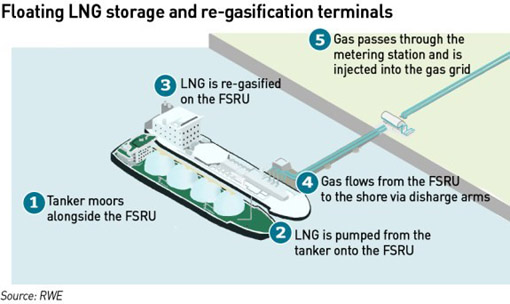

Germany is also getting into the LNG game – from having no terminals at all due to its long-term partnership with Russia, the country is now hurrying to construct two permanent terminals which are expected to be operational in 2026, and five floating LNG facilities each with a maximum capacity in the region of 5 bcm are planned to be operational by the end of the year.

Floating LNG terminals use vessels known as floating storage and regasification units (“FSRUs”) which re-gasify gas from an LNG tanker and inject it directly into the gas grid. While these are positive developments for Germany, they can only replace a portion of the 56 bcm of gas the country imported from Russia in 2021.

EU gas reduction plan aims to offset Russian volumes

EU member states have agreed to a voluntary gas reduction plan, to cut gas demand by 15% to the end of March 2023 in an effort to save 45 billion cubic metres (bcm) of gas, although it is estimated it might only save around 30 bcm due to various exceptions and derogations. This arrangement comes as gas prices in the TTF prices reached their highest level since March, and could become binding in an emergency if a majority of EU countries agree.

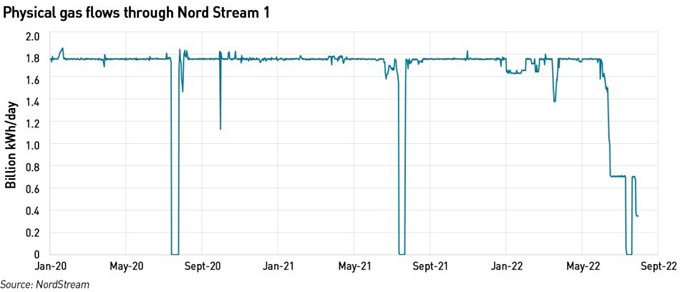

The concerns driving both the EU demand reduction plan and the Asian buying activity relate to the prospect of further reductions in Russian supplies to Europe, after Gazprom reduced exports through Nord Stream 1 to around 20% of its capacity, a move it blamed on delays in the delivery of a serviced turbine from Siemens. Gazprom’s Deputy Chief Executive Vitaly Markelov told Rossiya 24 TV that the unit had been expected back in May, but has yet to arrive. According to Siemens, Gazprom has not provided the relevant customs documents.

Last week German Chancellor Olaf Scholz was photographed in front of the elusive turbine which is now in Germany, but the German government and Siemens on one hand, and Gazprom on the other, seem to disagree as to whether it can be re-installed, with Scholz saying there is nothing preventing Gazprom from shipping the turbine back to Russia for installation, while Gazprom says western sanctions make this impossible. Tom Marzec-Manser, an analyst at ICIS, told the FT that most people in the industry view the turbine issue as a Russian-manufactured distraction, with Gazprom indicating that volumes on Nord Stream 1 will not rise above 20% and could fall further.

“Russia is claiming that there is only one operable turbine left for NS1, which at some point in the near future will need (or be said to need) to come offline for its own maintenance. At that point flows on the line to Germany could drop to zero,”

– Tom Marzec-Manser, analyst at ICIS

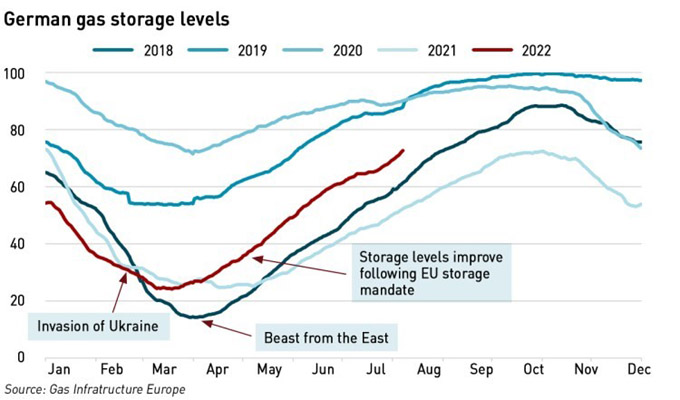

While German gas storage levels are higher than they were this time last year, with the cuts to Nord Stream 1 flows, it is now virtually impossible that the storage targets for the winter will be met. The unusually hot summer weather is boosting cooling demand across Europe, putting further strain on the system. Analysts are concerned that the resulting drought with low water levels and higher water temperatures is having a negative effect on cooling systems for nuclear power plants (as is also happening in France) and reducing the capacity of coal barges, which have to run lighter in an effort to sit higher in the water. This is raising demand for gas in the power sector, and recent weeks have even seen some storage withdrawals. One in six Germany companies has had to scale back production in response to the crisis, with more expected to follow suit in the coming weeks.

Storage levels across the EU continue to rise despite current high prices, and various EU countries are responding both to the demand reduction targets and to concerns over high prices with new regulations, although the measures are not always meeting with public support. In Spain, which is taking the strongest action, new regulations forbid businesses from cooling their premises below 27oC or to heat them above 19oC under a decree which is set to remain in place until November 2023. The decree also prohibits the illumination of monuments, bans shops from lighting up their windows after 10pm, and requires shops to have an electronic display showing the inside temperature to passers-by. France, which expects to have fully filled its strategic gas storage facilities by 1 November, is considering rules to prohibit shops from leaving their doors open while air conditioning or heating are running, and banning illuminated advertising in all cities between 1am and 6 am.

As Western buyers turn away, Russia pivots to Asia

Looking to the longer term, while western buyers and their governments see the reduction in energy supplies from Russia as a permanent shift, Russia itself would like to pivot to Asia and in particular China and India.

In 2021, Russia sold around 33 bcm of gas to Asia, far below the typical annual exports to Europe of 160 – 200 bcm (of which about 20 bcm is LNG). Two-thirds of the gas Russia sent to Asia was LNG: 14 bcm from the Sakhalin-2 project, going to Japan, Korea, Taiwan, and China, and 8.5 bcm from Yamal, serving mostly China, but also Japan, Korea, Taiwan, and India (with smaller volumes going to Bangladesh, Indonesia, and Singapore). Russia also delivered 10 bcm to China through the Power of Siberia pipeline, which was launched in late 2019 and will eventually reach an annual capacity of 38 bcm. Russian LNG destined for Europe can only be diverted to Asia in the summer when the northern shipping routes are free of ice (although technically they could make the long voyage round Europe through Suez. Altogether, using existing infrastructure, Russia could supply 80 bcm of gas to Asia.

There are new projects being planned which could increase this amount: the Power of Siberia 2 pipeline would connect the Asian markets to the existing European pipeline infrastructure, allowing gas previously destined to Europe to be diverted to China and beyond. This pipeline, with a possible capacity of 50-80 bcm /year could enter operations in 2030 if it goes ahead – but that is a big “if” – while Russia would be understandably keen to be able to arbitrage the European and Asian markets, it would need financial support for the project, and may not get a good deal from China:

“The problem, however, is that China holds all the cards in the negotiations. And like the first Power of Siberia line, China will drive a hard bargain. What is unknowable at this point is whether China is ready to make a deal. Russia is likely to offer very attractive terms—if nothing else, due to its desperation. But will China accept them? Will they be tempted by the price, or will they think twice about expanding their dependence on Russia at this moment? How the Chinese will answer these questions is hard to know,”

– Nikos Tsafos, the James R. Schlesinger Chair in Energy and Geopolitics at the Energy Security and Climate Change Program at the Centre for Strategic and International Studies

Russia is also planning new LNG projects, in particular Arctic LNG 2, which would double the country’s Arctic LNG capacity if it is fully completed: of the three trains, the first is almost complete and should begin operations next year, the second about half-built and the third only in the early stages. However, with Western construction partners pulling out of the project, a recent production projection from the Russian Ministry of Economy suggests that only the first train will become operational.

While Russia would of course like to diversify away from European buyers, whose decision to shun the country’s energy is likely to be permanent, it is unlikely to be able to replace these volumes for years to come, and may struggle to sell on the same terms European buyers have accepted. While China will certainly drive a hard bargain, Russia may find it easier to deal with India and Pakistan, and other countries which are being priced out of the LNG markets by European and richer Asian buyers.

Original article l KeyFacts Energy Industry Directory: Watt-Logic

KEYFACT Energy

KEYFACT Energy