Neivan Boroujerdi, Director, Research, Upstream Oil and Gas

Fraser McKay, Vice President, Head of Upstream Analysis

Norway has responded to calls to raise output and has an opportunity to grow and consolidate its position as a super basin of the future – but there are headwinds

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has pushed energy security to the top of the EU’s agenda. The pivot away from Russian imports has exacerbated the pressure on already tight oil and gas markets. Norway, Europe’s biggest oil and gas producer, has responded to calls to raise output. Its fiscal regime is appealing, and it leads the way on upstream decarbonisation. Its role as a supplier of choice seems cemented.

But can Norway seize this opportunity and maintain or even grow supply? Can it consolidate its position as an energy super basin of the future?

We drew on insight from Lens Upstream to explore this possibility in a new report: Can Norway maintain its role as an oil & gas supplier of choice? Fill in the form to read it in full, or read on for an introduction.

The call for Norwegian supply

The range of outcomes for oil and gas demand through the energy transition remains wide. But in our base case, demand in the EU is likely to keep growing until the mid-2030s. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has heightened the pressure.

Norway responded to calls to increase output by lifting production caps at flexible fields, redirecting gas from reinjection and accelerating infill drilling and debottlenecking. It’s now set to produce a record volume of gas in 2022.

And Norway is already a supplier of choice, due to its fiscal neutrality and its leading position in upstream decarbonisation.

Norway’s fiscal neutrality is appealing to upstream investors

While global oil and gas producers are realising record free cash flow, consumers are facing huge increases in their heating and fuel bills. Politicians in several countries are calling for windfall taxes – the UK’s Energy Profits Levy being the most high-profile change announced so far.

But investors abhor uncertainty. Norway’s commitment to tax neutrality and maintaining a stable investment environment – despite small fiscal tweaks – through previous cycles has not gone unnoticed. During the 2020 downturn, attractive fiscal incentives were introduced to protect and nurture investment. These incentives allowed accelerated depreciation and a higher uplift of development spend on projects sanctioned by the end of 2022.

It worked. Operators rushed to take advantage, committing to new projects and ensuring investment momentum until the late 2020s.

For more on how Norway’s fiscal regime affects upstream investment, download the full insight.

Norway is a global leader in upstream decarbonisation

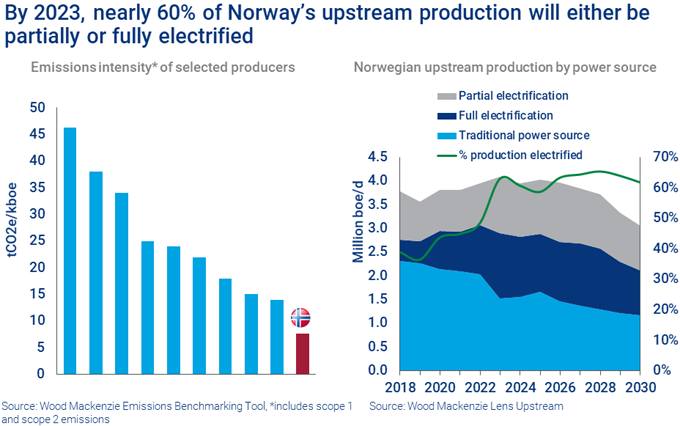

Norway has the lowest intensity of Scope 1 and 2 emissions of the most prolific oil and gas-producing countries, by some margin. At just 7 ktCO2e/boe, its aggregate upstream emissions intensity over the next decade are around a third of the global average.

With the highest proportion of electricity produced from renewables in Europe, Norway is a net electricity exporter and has been electrifying offshore platforms for nearly 30 years. By 2023, nearly 60% of its production will either be partially or fully electrified with power from shore or from floating offshore wind.

Norwegian emission taxes are also leading the industry. Already the highest in the world, the carbon tax on oil and gas producers is set to exceed US$260/tonne by 2030.

Can Norway’s current levels of output be maintained?

There are headwinds. Investment in the Norwegian sector has fallen from its peak in 2013 but spend has been maintained at around US$15 billion a year, largely underpinned by the giant Johan Sverdrup development. The temporary tax package introduced in 2020 gave the industry a shot in the arm. Projects – some previously considered marginal – have been revived and accelerated.

This surge of activity is putting pressure on the supply chain. Global upstream cost inflation is intensifying. First driven by the rising cost of raw materials, it is now being compounded by service sector capacity and supply chain constraints. While Norway’s fiscal terms provide flexibility to absorb cost overruns, long lead times and execution risk remain big issues to industry safety records, project economics and near-term supply.

Of longer-term concern is a thinning pipeline of development opportunities. While current levels of production are likely to be maintained to the late 2020s, underwhelming frontier exploration results – particularly disappointments in the Barents Sea – have taken their toll. Beyond 2022, there are very few greenfield projects in the pipeline.

Waning interest in the basin has been exacerbated by the shift in the corporate landscape. Consolidation has halved the number of active producers in recent years and there are question marks on whether the current crop of players have the appetite, financial capacity or expertise to unlock the complex developments required to maintain sector momentum.

All to play for: Norway’s place among the energy super basins of the future

Longer-term, the world’s growing need for sustainable energy will change the geography of oil and gas. For the upstream industry to become more sustainable, it must focus on resources in locations with both plentiful clean electricity and CCS potential – the geological super basins of the future.

Norway already has an electrification advantage, and is an early-mover on CCS. There is a clear opportunity to grow and consolidate its position.

KeyFacts Energy Industry Directory: Wood Mackenzie

KEYFACT Energy

KEYFACT Energy