How Rowett Institute scientist David Lubbock devised some of the earliest energy bars to supply the daring escape efforts of Prisoners of War

By Jo Milne, Communications Officer, University of Aberdeen

In the darkness of March 24, 1944 dozens of servicemen began their descent into tunnels to flee a prisoner of war camp which inspired the film The Great Escape. Their story has been well documented but what has largely gone under the radar is the work of Rowett Scientist David Lubbock, who created some of the earliest known energy bars to fuel the daring exploits.

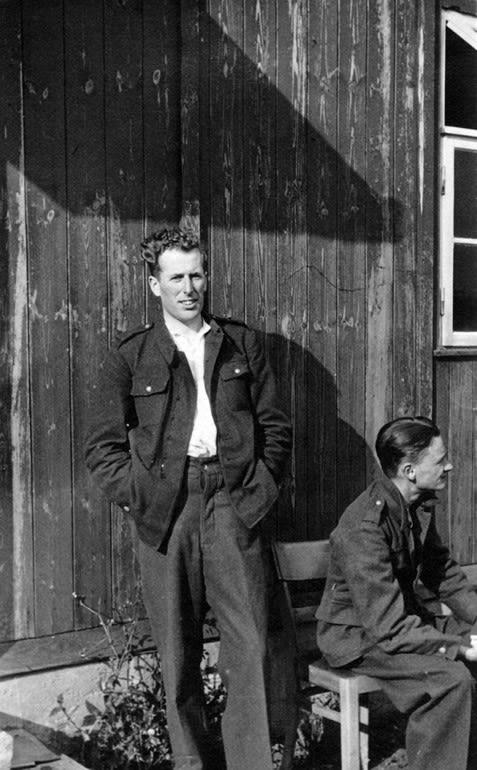

David Lubbock as a prisoner of war

A man of science who volunteered for the war effort

Born in Surrey in 1911 Lubbock obtained a degree in Nutrition and Economics from Trinity College Cambridge and joined the pioneering founder of the Rowett Institute, John Boyd Orr, in Aberdeen in the early 1930s. He worked in various laboratories in the Institute and then as a member of the research team on the ground-breaking Carnegie Survey, which investigated the relationship between diet and health in Scottish and English families and examined the effect of improved diet on children’s health.

His ties to Boyd Orr strengthened further when he married his daughter Minty shortly before the outbreak of the Second World War in 1939.

When war commenced Lubbock enlisted with the Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve and was sent to gunnery school in Portsmouth. His personal documents held in the University’s Special Collections reveal that he ‘like everyone else wanted to be a pilot’ but his eyesight was not good enough and so instead he was given the role of observer. He writes that he did question how much better suited this post was to someone with poor eyesight but never received an answer!

In July 1941 Lubbock was part of a mission which saw HMS Victorious and HMS Furious (which Boyd Orr had also served on during World War I) used to mount an attack on Nazi shipping in Kirkenes in the far north of Norway, to help Britain’s new ally the Soviet Union.

As an observer he joined a pilot and gunner abord a single-engine Albacore plane. He describes how having let off their torpedoes, they turned to get out of Kirkenes Harbour when their aircraft was hit by enemy fire.

The air gunner died in his arms and Lubbock was showered with metal splinters, one of which nicked his supraorbital artery, causing him to lose first his colour vision and then his eyesight completely.

His medical understanding came to the fore - and not for the last time during the war – as he was able to stem the bleeding with his finger and his vision returned.

But the plane was too damaged to land back on HMS Victorious and ‘still under attack until the enemy ran out of ammunition and with more bits falling off the aircraft’, the pilot made an emergency landing in the tundra.

Weak, and still with three metal splinters sticking out of his eye, he and the pilot began a long trek east in a bid to reach Russian lines.

With nutrition always at the forefront of his mind, he describes how he tripped and fell but on lying on the ground found a welcome covering of blaeberries.

But a meeting with a lone ice fisherman proved fateful and instead of leading them to Russian lines, he was turned over to German soldiers and became a prisoner of war.

He again used his scientific background to strike up a rapport with a German medical officer who removed the splinters from his eye and who he credits with saving his eyesight.

Escape on the mind

Lubbock was taken by plane to Oslo and then on a train through Sweden, into Denmark and south towards Germany.

He already had escape attempts on his mind but was too weak to attempt the ideas he was formulating during the journey.

At a transit camp he met the famous aviator Douglas Bader – a double amputee celebrated for his role in the Battle of Britain.

They had fallen into enemy hands on the same day and were both travelling alone. The pair soon struck up a friendship and ‘as the nearest to a medical doctor’ Lubbock helped Bader care for his ‘legs’.

In a letter written on his 90th birthday Lubbock describes how he and Bader immediately set about ‘a feeble and amateurish’ escape tunnel at the holding camp.

When reunited by the television programme This is Your Life, Lubbock tells the audience how they used Bader’s hollow legs to transport soil in a bid to disguise the dug up earth!

They were then sent to different camps, Bader to Colditz and Lubbock to Szubin in Poland. In Spring 1942 he was moved to the ‘escape proof camp’ Stalag Luft III.

Feeding the escapees

Stalag Luft III’s status as ‘escape proof’ served only to intensify the efforts of its inmates, whose audacious, real-life prison break was immortalised in the 1963 movie The Great Escape and the 1949 book The Wooden Horse.

But while the tunnel digging feats have been well covered, the work of Lubbock and others to fuel the exploits have received little attention.

Lubbock’s own notes written in small handwriting on browning paper held in the University’s archives offer insights into the extensive planning that went into food provisions.

He writes: “In the early days many escapees prepared food to take with them which was too rich in fats and difficult to digest which in time became nauseating. Thus there sometimes arose the somewhat strange situation of a POW unable to hold down chocolate even though ravenously hungry.”

Lubbock set about changing that. In other notes he documents that: “With the help of Flt Lt Von Rood, a Dutchman and keen experimenter who later made a brilliant escape only to be caught on the Swiss border, we managed to produce two forms of fudge that suited escape requirements….One based mainly on cocoa and the other on Bemax (a wheatgerm cereal)…which gave a balanced ration and provided as well as we could for all conditions of feeding outside the wire.”

They also produced a dry nutritional powder which could be carried and then mixed with water.

Making – and more importantly storing – these high energy concoctions made from Red Cross food parcels, which became the standard escapee ration, was a game of cat and mouse with the camp guards.

Those charged with uncovering contraband were known to the inmates as ‘ferrets’ and when asked after the war to provide details of security arrangements, Lubbock details the ingenuity of the hidey holes created, including one in the guards’ own staff room which was not searched as it was locked and regarded ‘safe’.

Lubbock was one of three security heads for the escape committee – the only men who knew the location of all the tunnels. As part of this he had to ‘give up’ the poor tunnels to prevent the ‘good’ tunnels being found, though the tunnelers never knew that they were sacrificed by the security team.

This meant that inevitably some of the energy bar stocks were also discovered and Lubbock was later told that one Christmas German children had been given the confiscated ‘fudge’ as a treat.

While much of Lubbock’s time was taken up with escape committee matters, he continued to promote education setting up a small library for the camp with the help of the Red Cross, giving lectures on nutrition to interested inmates and helping those hoping to take or complete medical degrees.

He continued to document his research and ideas, compiling his small notes into a hidden book. The Germans sought to utilise his nutritional expertise and when he refused, Lubbock was punished by being sent to ‘the hole’.

When the fateful day for The Great Escape came (March 24, 1944) Lubbock had sprained his ankle and so gave up his right to escape to a more able prisoner.

Although 76 prisoners successfully made it past the wire, 73 were recaptured following a massive manhunt. A furious Adolf Hitler personally ordered the execution of 50 of the escapees as a warning to other prisoners and Lubbock later told of how the ‘ferrets’ (guards) came and wept with the remaining prisoners in the camp.

The long march to freedom

By the end of January 1945 Russian forces had advanced to within a dozen miles of Stalag Luft III and it was the guards that would enact the exit of Lubbock and hundreds of other POWs from the camp.

Clothes and rations were hurriedly packed and many personal possessions abandoned in the scramble to evacuate the camp.

With science always at the forefront, Lubbock took with him the research which had occupied his mind during his three and a half years in captivity.

He kept it safe during the long and freezing trek away from the Russian advance as the POWs were marched miles into Germany through villages which offered little shelter and with only limited rest. They stopped to regroup at the old Medieval spa town of Muskau.

Fearing that his precious research would be taken from him, Lubbock took the chance to hand it over to a French priest who he asked to get it ‘somehow, sometime to the UK’. The clergyman was true to his word and a number of years later it arrived carefully packaged at Portsmouth barracks.

Marching on to the rail hub of Spremberg the POWs were loaded into overcrowded cattle trucks and taken to other camps.

Incarceration in Germany was short lived as the allies swiftly advanced and after three and a half years Lubbock was finally returned home to Aberdeen, where we hope Boyd Orr was true to the letter he had written him in December 1944 that ‘a jar of marmalade still waits for you and plum pudding’.

The lessons learned from hunger

After the war Lubbock returned to the Rowett before he was once again recruited by Boyd Orr, this time to support his work as the first Director General with the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO).

The FAO was established to support agricultural and nutrition research and production in agriculture, fishery, and forestry.

There he was promptly nominated by his father-in-law to put together an assessment of the current world food situation – and given a deadline of just four months. Something he described as ‘a terrifying responsibility’ given Boyd Orr’s instance that they demonstrate to world leaders that ‘the world should not turn a blind eye to the gathering famines due to war and post-war disturbances of food production and supply’.

As the First Secretary to the Director General of the FAO Lubbock played a major role in the logistics and organisational planning for conferences to unite member countries and highlight global issues of food security.

He later worked in Indonesia, Mexico and Zambia for FAO and United Nations Development Programme, eventually retiring to farm in Scotland.

Lubbock’s experience as a POW offered him insights into the devastating impact of food shortages and strengthened his commitment to eradicating hunger. He wrote: “It is said people will go to any lengths for food but one has to experience real shortage to realise the full meaning of those words. It helps one to realise how easy it is when there is a lack of needs and how different it is when hunger gnaws continually.”

Original article l KeyFacts Energy Industry Directory: University of Aberdeen

KEYFACT Energy

KEYFACT Energy