By Kathryn Porter, Watt-Logic

For the past year Ofgem has been trying to address concerns around the financial resilience of energy suppliers after half of them went bankrupt in late 2021 following the rapid increase in wholesale prices. Ofgem has been strongly criticised for allowing suppliers to enter the market with insufficient capital to absorb even minor losses, and while creating new barriers to entry is relatively simple, dealing with existing suppliers is much less so.

Last summer Ofgem consulted on measures that would require suppliers to ringfence Renewables Obligation (“RO”) payments and customer credit balances (“CCBs”), as well as maintaining adequate capital. Some suppliers, led by Centrica, were strongly in favour of these proposals, since when a supplier fails, these particular costs are often socialised, ie suppliers that did not fail end up having to meet the failed supplier’s RO payments and the restoration of its customers’ credit balances. Others, led by Octopus Energy, strongly opposed the proposals on the basis they would increase costs and therefore make energy more expensive for consumers. It would also risk reducing competition. These objections are both true – the changes would indeed have those effects – but that does not necessarily mean they should not be implemented since these disadvantages could be out-weighed by the benefits of a more financially resilient sector.

In any case, Ofgem was discouraged from pursuing its proposals, and in November launched a further consultation, this time, while ringfencing RO payments was retained, and specific capital requirements were set out, the ringfencing of CCBs was replaced with an enhancement to the existing Financial Responsibility Principle to embed a minimum capital requirement for domestic suppliers, and introduce a positive obligation on them to evidence that they have sufficient business-specific capital and liquidity to meet liabilities on an ongoing basis. This watered-down proposal was met with the opposite reactions to the previous one, with Centrica and E.On opposing it and Octopus being supportive, although not all challenger suppliers agreed, with Utilita in particular disagreeing with the new stance on CCBs while some larger suppliers such as EDF were supportive.

Now Ofgem has confirmed its decision to require the ringfencing of RO balances and the creation of the Enhanced Financial Responsibility Principle (“eFRP”), and has launched yet another consultation on capital requirements and ringfencing CCBs. The response deadline for this new consultation is 3 May 2023.

RO ringfencing will go ahead in line with the November proposals

Stakeholder feedback to the November 2022 consultation was mixed, although almost all stakeholders recognised the need to address financial resilience in the sector. RO ringfencing was also broadly supported with stakeholder views primarily divided on speed of implementation – objections generally focused on the impact ringfencing would have on supplier cash flow.

A consistent theme from many respondents was the need to consider these proposals alongside other potential changes in regulation, particularly “the need to support the investability of the sector through reform of the EBIT allowance in the energy price cap”. In other words, the costs of adopting these measures need to be reflected in the EBIT allowance otherwise supplier profitability and therefore their ability to secure capital, would be at risk. Ofgem accepts this and says it will take these issues into account when setting the EBIT allowance in the price cap.

Some respondents objected to the proposals altogether. One provided no reason for its objections. One said that there is currently no appetite for lenders to invest in the retail energy sector, and it would take years of sustained profitability and a steady return on investment to change this, rather than additional regulation. Another claimed the proposals unfairly benefit legacy suppliers who have lower costs of capital.

On this note, one respondent supported the proposals but said they would place “significant stress” on some suppliers, potentially leading to further failures, and that there should be greater flexibility for smaller suppliers whose market impact is also smaller. They argued that smaller suppliers “drive innovation and competition in the sector”. However, another supplier argued the opposite saying that anything other than market-wide application would defeat the whole purpose of the change and undermine competition. This is a good point because the large legacy suppliers are not the ones which are most at risk of failure, so while their failure would have a large market impact, they are significantly less likely to fail than challenger suppliers.

In March 2023 Ofgem published draft documents to support the operationalisation this new requirement:

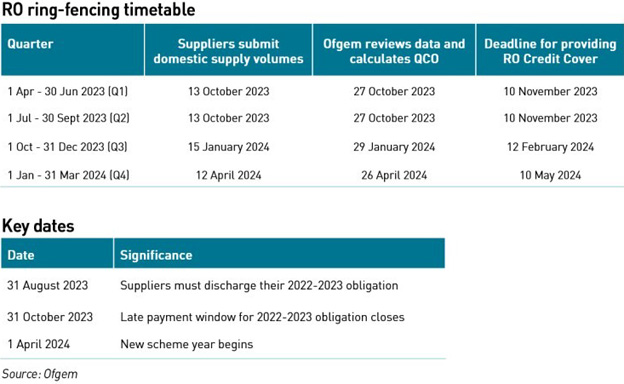

- Draft RO ringfencing schedule setting out the key dates and deadlines for the ringfencing process for 2023/24 scheme year;

- Draft Supplier guidance for the new ringfencing licence condition explaining what licensed electricity suppliers would be required to do to ringfence their RO receipts. It described how the Quarterly Cumulative Obligation (“QCO”) will be calculated, as well as when and how proof of ringfencing would need to be evidenced;

- Draft templates for the Protection Mechanisms – draft templates for Standby Letters of Credit, the First Demand Guarantees, and terms for Trust Accounts and Escrow Accounts to standardise the approach to ringfencing and streamline administration for both suppliers and Ofgem.

RO ringfencing is now being implemented, with immediate effect. Suppliers will need to provide evidence of having ringfenced their RO receipts for Quarters 1 and 2 of the 2023/24 scheme in Quarter 3 (November 2023) and for each quarter thereafter. Ofgem has removed Escrow Accounts from the list of protection measures.

“As a general point of principle, we do not think that competitive advantage arising from financial strength is a problem in itself,”

– Ofgem

Ofgem believes it is reasonable to allow suppliers to recover the costs of ringfencing RO receipts through a temporary increase in the price cap allowance until the EBIT decision made and implemented. This will cover the cost of obtaining credit cover which is being set at the CMA’s assumption of a 10% WACC, although in its response to the November consultation, Utilita suggested that the CMA’s model contains errors, saying “Ofgem has already implicitly admitted by its actions in increasing the prepay price cap in October 2019 that the CMA price cap model was erroneous and did not reflect the efficient costs of supply”.

Under the price cap legislation, Ofgem is not allowed to set supplier-specific price caps or different caps for different business models. This means some suppliers may over-recover and some under-recover these (and other) costs under the cap – Ofgem believes suppliers in stronger financial position will be more competitive and that this is appropriate.

The eFRP imposes additional reporting requirements and capital targets for suppliers

The current FRP requires suppliers to manage costs that could be mutualised responsibly, and to take appropriate action to minimise such costs. This means demonstrating – among other things – sustainable pricing to cover costs over time, and that risks of any pricing strategy sit with investors and not consumers; robust financial governance and decision-making frameworks; and the ability to meet financial obligations while not being overly reliant on customer credit balances for working capital.

In November, Ofgem proposed requiring suppliers to maintain sufficient capital and liquidity to ensure they could meet anticipated liabilities as they fall due. Its initial proposal was that this would complement a ‘Pillar 1’ minimum capital requirement to enable a supplier to manage its business specific risks and ‘Pillar 2’ aimed at managing severe but plausible stress scenarios. Supplier self-assessment reporting regarding business-specific risks was proposed to help Ofgem understand if further interventions would be necessary. Ofgem proposed to apply the eFRP to both domestic and non-domestic suppliers, except for specific elements relating to the common minimum capital requirement and directing ringfencing of CCBs. Monitoring for non-domestic suppliers would be proportionate to the risk of mutualisation.

The eFRP would require suppliers to:

- Ensure they maintain sufficient capital and liquidity to meet their reasonably anticipated liabilities as they fall due, to include maintaining a common minimum capital requirement;

- Ensure that, were they to exit the market, the exit would be orderly. This would mean suppliers must ensure operational and financial arrangements are such that any Supplier of Last Resort or special administrator would be able to effectively serve its customers, and the exit would not result in material mutualised costs.

- The FRP would be further strengthened by having financial reporting with trigger points to act as early indicators of financial stress. Suppliers would have to proactively report to Ofgem on how they were meeting requirements for ongoing financial resilience and to flag where risks arise, with more opportunities for early intervention by the regulator. This meant notifying Ofgem if they became aware of not being able to hold the common minimum capital requirement or if any of the trigger points might be hit. This framework would also be used for enhanced monitoring of reliance on CCBs and make it easier for Ofgem to intervene (eg through engagement, enhanced monitoring, requesting an independent audit, direction to protect CCBs, or enforcement action to ensure compliance with the FRP).

Finally, the proposal also included a requirement for suppliers to submit an annual self-assessment of their business model, risks and mitigations over the previous 12 months and the coming year, evidencing their compliance with the enhanced FRP.

Most stakeholder responses were supportive, but there were views that the enforcement proposals relied on a discretionary approach and supplier self-assessment. Respondents said Ofgem would need to improve its resourcing for processing and reacting to the enhanced FRP data received from suppliers. There was also concern regarding the amount of data suppliers already report to Ofgem and that further information requests may be burdensome. One supplier suggested that the proposals were disjointed, and didn’t fit into a coherent framework. A minority of suppliers suggested the eFRP and minimum capital requirement should interact to reduce the capital requirement on firms reduce the residual risk in their businesses.

“…we have decided to establish an enhanced Financial Responsibility Principle, changing the culture of reporting by placing the onus on suppliers to identify issues early, mitigate their business-specific risks and look longer term how they will comply with their obligations. We are also creating a market-wide obligation for suppliers to ringfence Renewables Obligation (RO) receipts attributable to domestic supply, aimed at reducing the risk of misuse of these receipts as cheap working capital,”

– Ofgem

Ofgem has decided to implement the eFRP broadly in line with the November proposals, but with some changes as follows:

- Clarificatory changes to the licence condition: including removing references to the common minimum capital requirement pending the outcome of the latest statutory consultation;

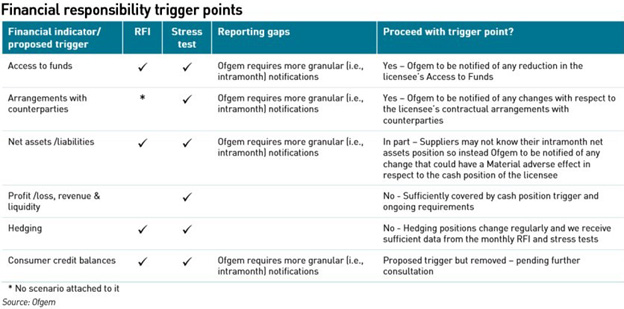

- Triggers framework: reducing the number of trigger points and clarifying that complying with them is a licence requirement. Ofgem is also consulting further on the details of the CCB trigger;

- Annual Adequacy Self-Assessment: clarifying that this is a licence requirement; improved clarity on the self-reporting process.

These rules will require suppliers to take action to ensure that:

- They maintain sufficient capital and liquidity to meet their reasonably anticipated financial liabilities as they fall due;

- If they were to exit the market, any Supplier of Last Resort or special administrator would be able to effectively serve its customers and that mutualised costs would be minimised;

- Costs that could be mutualised are managed responsibly and minimised;

- They have adequate financial arrangements in place to meet costs at risk of being mutualised at all times; and

- They maintain sufficient control over any material and economic asset used to meet their obligations and do not dispose of said assets if doing so risks an increase in costs at risk of being mutualised.

In their annual self-assessments, suppliers will need to explain how they determined the appropriate level of capital and liquidity they require to be compliant with the eFRP, and explain their business plan and the business-specific risks they expect over the coming 12-months. The assessments might include the following elements (although Ofgem is not specifying the exact form these assessments should take):

- How the supplier is funding regulatory obligations;

- The supplier’s risk appetite associated with its business strategy, eg tariff pricing, hedging strategy, purchasing agreements;

- Identification and explanation of all material business-specific risks, and an evaluation of the associated mitigation strategies;

- Terms of any purchasing agreements, and the risks and mitigations associated with those terms;

- Reliance on the balancing market;

- Collateral requirements;

- Description of internal processes for identifying and mitigating risks;

- Details of stress-testing of business projections and risks;

- The sources of capital used to fund the business and meet the requirements of the eFRP.

The first self-assessments must be submitted by 31 March 2024.

Ofgem has provided further clarity around its response to a trigger notification. This will depend on the circumstance, but might include enhanced monitoring or requesting that the supplier stops making non-essential payments. Ofgem is consulting further (see below) on the use of trigger points to require ringfencing of customer credit balances.

Ofgem recognises that it has increased reporting requirements on suppliers so is choosing to introduce a “low frequency, high detail” reporting requirement, and believes that suppliers themselves are best placed to analyse the risks they face and whether they have adequate capital to meet them. The new model of reporting is intended place more responsibility on suppliers to assess their own risks and the effectiveness of their mitigations. Some smaller suppliers such as Ecotricity expressed concerns in the November consultation around the reporting burden. At the opposite end of the spectrum, EDF urged Ofgem to digitise its information requests to automate the process and thereby reduce the burden on suppliers.

“…the level of information required within the Annual Self-Adequacy Assessment…needs to be proportionate to the size of the business and should remained focussed on the deliverables of financial adequacy. We hold concerns that this self-assessment process could create wider inefficiencies in practice, leading to an increase in our cost base…We also note the background to this consultation including an “avalanche” of recent information requests. Whilst we understand this in the context of the fallout in relation to the energy crisis, information gathering and the process of ensuring supplier compliance with the FRP must be balanced,”

– Ecotricity

At the most basic level, competent directors should be assessing their business risks and holding adequate capital, and those that are not competent, fail. However, since some of the costs of failure within the retail energy market are socialised, the regulator needs to mark their work, to ensure the impact of supplier failure on consumers more broadly is minimised.

However, as with all such regulatory checks, there will be difficulties. One relates to the workload all of this marking will involve for Ofgem. The other is whether Ofgem have the expertise to evaluate the information they receive appropriately. For suppliers with simple business models, this should not be too taxing, but where suppliers have more complex operations, Ofgem might struggle. How will it evaluate the risks associated with proprietary trading for example? Will its view of hedging change depending on whether the supplier uses hedge accounting or not? How will contingent risks and off-balance sheet instruments be treated? How will counterparty credit risk be assessed? What about companies which mix supply and non-supply activities within the same legal entity…how will Ofgem assess the business risks of activities which may be outside its sphere of expertise?

E.On raised concerns in the previous consultation about the entire concept of self-reporting by suppliers, warning that where suppliers are facing difficulties they may opt not to self-report these to Ofgem, or they may have an overly optimistic view on their position and reflect that mis-placed optimism in their reporting to Ofgem. It also noted that once a supplier did report potential financial distress, Ofgem may be unable to take effective action, and requiring the ringfencing of CCBs at that point may actually cause further financial distress, making failure more likely.

“…a supplier that is struggling to survive is unlikely to be concerned by the threat of enforcement action – if it’s failing anyway, it has nothing to lose by gambling to survive.”

– E.On

Of course, the fact some of this might be difficult does not necessarily mean it should not be done, but there are two main risks: one is that Ofgem fails to evaluate the information it receives correctly, and the problems with mutualised costs continue. The other is that in seeking to avoid those risks, Ofgem starts to define what supply business models should be either directly or indirectly, thereby harming competition and innovation.

“Suppliers will all need to act like Ofgem’s notional supplier in order to survive (whether than be making a return under the price cap or being able to meet capital adequacy requirements). We note that in other markets, capital adequacy requirements have flexibility built in that reflect the risks a particular company incurs because of the way it runs its business but based on a common framework. For example, a supplier who decides not to hedge is by default taking more risk than a supplier that hedges and should face a higher capital adequacy requirement to account for this. Aligning a one-size-fits-all capital adequacy requirement to a one-size-fits-all price cap leads the market down a path toward limited, if any, competition in future,”

– E.On

Indirect regulation of business models is already inherent in the price cap, since suppliers must implement hedging strategies that closely mirror the price cap methodology to be confident of recovering their wholesale costs under the default tariff. Indeed, Ofgem recognises this it its EBIT consultation, saying “…suppliers would have had more control over their hedging had there not been a cap – providing them more options to manage their risks”.

There is limited scope, given low the low EBIT allowance of just 1.9% for suppliers to adopt different pricing strategies, which has resulted in suppliers offering default tariffs that cluster tightly around the level of the cap, thereby reducing consumer choice. Restrictions on regulatory capital will apply similar pressures to supplier funding models, and may drive similar effects in the other tariffs offered by suppliers.

Some sensible minimum capital proposals but triggers may be unworkable

The market responses to the proposals in November for a common minimum capital requirement and for directed ringfencing of consumer credit balances were much broader and so Ofgem has decided to engage in further consultations on these two areas.

“Your consultation presents a worrying picture of an environment where some suppliers have zero net assets, raising capital is potentially extremely difficult and expensive, and it may take many years for suppliers to be adequately capitalised. The multiple year transition approach you suggest implies that you do not think the sector would be able to withstand quicker reform; that trying to ensure its financial sustainability more quickly would, ironically, threaten its financial sustainability,”

– Citizens Advice

In particular, some stakeholders raised questions around the use of capital in response to shocks – since the purpose of holding this capital is to act as a buffer in case of market shocks, there should be sensible rules around how the levels are adjusted in response to market conditions, allowing suppliers to be temporarily below the minimum capital requirement where loss-absorbing capacity is used to absorb losses, and the amount of time suppliers would be allowed to re-build these buffers should some of them be used up during a shock.

Ofgem would like to add capitalisation requirements to the eFRP as follows:

- From 31 March 2025 onwards, their adjusted net assets must not fall below the capital floor, and;

- From 31 March 2025 they should meet the capital target or have a capitalisation plan in place that sets out how they will meet the capital target.

Capital floor: the capital floor will be equivalent to £0 per domestic dual fuel customer at any time. Suppliers will set out how they are meeting the capital floor in their annual adequacy self-assessment but they are expected to be able to demonstrate on an ongoing basis that they are not in breach of the floor. Suppliers must notify Ofgem in writing as soon as reasonably practicable, and not more than seven days, from the time they become aware they have fallen below the capital floor or if there is a material risk of doing so.

Capital target: domestic suppliers will be expected to meet, or be on a path to meet, a capital target equivalent to £130 adjusted net assets per domestic dual fuel customer.

Ofgem would prefer that suppliers meet the capital requirements using equity where possible, however, since adequate levels of resilience can be provided by non-equity capital, suppliers can use these if they can demonstrate this funding meets certain criteria set out in the rules. Adjusted net assets should be the same net assets as reported in the supplier’s statutory accounts plus any alternative capital such as:

- unsecured shareholder loans not subject to accelerated repayment conditions, with a minimum 12-month residual maturity;

- working capital facilities from a counterparty with a minimum credit rating of Baa3/BBB- or equivalent, with a minimum 12-month residual maturity provided that it is not subject to full repayment and/or cancellation condition; or

- unconditional, quantifiable general guarantees from a related party with a minimum credit rating of Baa3/BBB- and a minimum 12-month residual tenor.

Ofgem is now consulting on the introduction of the capital floor and capital target from 31 March 2025, the size of the initial levels of these measures, and the use of capitalisation plans to manage compliance. It is also consulting on calculating the target based on the number of accounts for each fuel (ie £65 per account) recognising the risk of over-insurance where some customers only contract for a single fuel only with a supplier, and the definition “capital”, including criteria for off-balance sheet funding.

In November, Ofgem consulted on a range of £110 – £220 per dual fuel customer as the basis for the minimum capital requirement, which has now been adjusted to £130, split equally between gas and electricity on a single fuel basis. EDF was of the opinion that £100 would be the maximum necessary for “an established and stable supplier” while ScottishPower felt the range was too low:

“We think the proposed range of minimum capital (£110 to £220 per customer) is too low and when coupled with the two year implementation period will prove a very weak protection against suppliers pursuing financially irresponsible and unsustainable business models,”

– ScottishPower

The timeframe for compliance reflects that previously described in the November consultation. Centrica in particular objected to this long lead time:

“In our response to the [July] Policy Consultation we said that Ofgem needs to bring forward it’s proposed capital adequacy framework as soon as possible…It is therefore disappointing that Ofgem is proposing a long transition period. This transition period means that the capital adequacy framework offers no near-term protections to address the moral hazard identified by Ofgem and still present in the energy supply market. Combined with a lack of protection for CCBs this means that Ofgem has not delivered for consumers who remain exposed to the risks and costs of supplier failure,”

– Centrica

Ofgem believes that the consequences of not meeting the capital floor and capital target are different, with failing to meet the floor being significantly worse. It therefore proposes that allowing capital to fall below the floor would be treated as a serious breach of a supplier’s licence conditions that could, if not remedied, lead to the licence being revoked. Suppliers comply with the floor but not the capital target would not be in breach of the licence condition but would be subject to additional controls.

This means that if a supplier’s capital falls below the target level as a result of a market shock, it would not be in breach of its licence conditions and would have time to re-build its capital base. However, Ofgem believes suppliers should never allow their net asset position to become negative as this would represent too high a risk of cost mutualisation. Where suppliers fail to meet the capital target, they will need to submit a credible capitalisation plan setting out how they plan to achieve the target and over what timeframe. After the plan has been accepted by Ofgem, the current proposal is that the supplier would submit quarterly progress reports. Failure to adhere to the plan or meet agreed quarterly milestones would be a breach of the licence condition and could result in enforcement action.

Where a supplier is below its capital target it may (but not necessarily) also be subject to transition controls, which Ofgem proposes to include a restriction on sales, marketing and customer acquisition activity, and a ban on non-essential payments. Ofgem might also seek an independent audit of the supplier.

E.On criticised similar proposals in the November consultation, suggesting they would be unenforceable, and that owners of a supplier facing difficulties may withdraw money from the business before informing Ofgem of those difficulties. A ban on non-essential payments would come too late, particularly as suppliers would be aware that once they reported the problems, such a ban would be likely.

“Should a supplier experience financial challenges, there is a real risk that it will seek to extract value from the business as swiftly as possible for their own gain. Actions like these were reported during the many supplier failures of 2021. Ofgem’s proposals would not prevent a supplier from taking these actions in future (it might simply change the actions or timing of actions), leaving the related costs to be mutualised should it become insolvent. We urge Ofgem to make the most of the insight it can gain from regular, meaningful reporting,”

– E.On

Ofgem is consulting on the definition of capital to be used and how intangible assets should be treated. Based on an analysis of suppliers’ accounts files at Companies House, Ofgem has identified that the fixed assets of some suppliers consist of more intangible than tangible assets, which are difficult to both value and monetise. There are legitimate reasons for not allowing suppliers to rely on intangible assets as part of their loss-absorbing capital, however they are recognised as part of the value of a company and there are downsides to making the definition of capital too complex. Ofgem is considering whether any classes of intangible assets should be excluded from the definition of net assets.

EDF rejected the use of net assets as the measure of capital in its response to the November consultation, pointing out that some fixed assets are illiquid and cannot easily be monetised, and some assets might make a supplier less resilient if they were liquidated. It also pointed out that suppliers might change their accounting policies in ways that would artificially increase the value of assets in order to meet capitalisation targets:

“A Fair Value derivative asset related to a hedge book of purchase commodity trades gives a false impression of financial resilience, as it implies that a supplier could meet liabilities by unwinding its hedge position – which would in fact reduce its financial resilience… A net asset test could lead to an incentive to adopt accounting policies which may lead to inappropriate capitalisation of assets or accelerated revenue recognition.”

Centrica also pointed to the importance of liquidity, highlighting that the banking crisis of 2008 was driven by insufficient liquidity not inadequate capital.

Ofgem is also considering what a reasonable minimum tenor or expiry date for a parent / group working capital facility, shareholder loan or guarantee would be for it to be considered as long-term loss absorbing capital, and whether there are any additional debt instruments available in the market that should be included in the definition of capital.

Targeted ringfencing of consumer credit balances may be difficult to apply in practice

On the subject of ringfencing consumer credit balances, Ofgem now believes that full market-wide ringfencing would be inefficient and that consumers should expect that some of their credit balances should be used for working capital in line with other industries such as travel and durable consumer goods, in contrast with the RO which is a simple pass-through. Instead, Ofgem is proposing to instruct individual suppliers to ringfence CCBs if it considers they have an “over-reliance” on them.

Of course, this risks being subjective. In addition to potentially directing a supplier to ringfence CCBs if it is not meeting its capital target, Ofgem is also considering requiring them to do so if they are not maintaining enough cash to honour customer requests to repay credit balances at a level that might be expected in a severe but plausible switching scenario and when a high volume of refund requests is received. Specifically, Ofgem is proposing a cash coverage condition to require suppliers to maintain monthly cash (in the bank) balances of at least 20% of gross CCBs net of unbilled consumption owed to their fixed direct debit customers. However, Ofgem would have discretion over the level of ringfencing it would direct, being anywhere between 0% and 100% of such balances.

In its response to the November consultation, Centrica complained that Ofgem had not justified why an efficient notional supplier would use CCBs as working capital – it still has not done so in this consultation beyond re-iterating its belief that this is the case. Indeed, Centrica pointed out that this contradicted Ofgem’s own previously held position that suppliers should not use CCBs for working capital:

“We consider Ofgem’s U-turn on the issue of the protection of credit balances to be an appalling missed opportunity; if adopted, we consider the regulator to be guilty of gross negligence in the discharge of its duties and obligations to consumers. Ofgem’s established and very public position has long been – quite rightly – that the use of customers’ monies to fund working capital by energy suppliers is akin to using “interest free company credit cards”. Yet Ofgem is now suggesting that using customers’ credit balances is acceptable behaviour up to a certain point, beyond which such behaviour becomes unacceptable once more. This is a position that strains the bounds of credibility… Ofgem has set out no clear rationale for its position that the use of customers’ monies to fund working capital is an acceptable practice, aside from an oblique, unexplained and highly specious references to practices in the “travel and durable consumer goods” markets,”

– Centrica

Centrica went on to say that if Ofgem persisted in not mandating the ringfencing of CCBs, it should direct suppliers to disclose to their customers how and why they use their credit balances for working capital. Age UK was also sceptical of the decision not to require all suppliers to ringfence all CCSs, whereas Utility Warehouse would prefer suppliers to be banned from accepting advance payments, describing the practice as “discredited”.

Citizens Advice was also concerned by the November proposals, and in particular the discretionary aspects, raising doubts over Ofgem’s competence given previous, well documented enforcement failures.

“This discretionary approach worries us, as it relies heavily on Ofgem’s ability and willingness to identify problems and step in. Our Market Meltdown report highlighted that Ofgem reduced its enforcement headcount during the years when unsustainable suppliers were entering – and often subsequently chaotically leaving – the market,”

– Citizens Advice

It’s interesting to note the strength of Octopus Energy’s opposition to Ofgem’s original proposals for market-wide ringfencing of gross CCBs. During the discussions with Teneo and Lazard last spring around the sale of Bulb, its feedback on the regulatory context was revealed in the recent judgement as:

“Topics that Ofgem has still not provided clarity on make this sector very risky. Ofgem has not yet resolved the backwardation issue and the potential ringfencing of credit balances could mean that soon retail could be of no interest even to us …buying in this context doesn’t make sense…”

At the time of the previous consultations, Octopus had strongly opposed market-wide ringfencing of gross CCBs, on the basis that it would be inefficient, expensive for consumers and would unduly distort competition by favouring suppliers with larger balance sheets. However, the idea that the change, together with a failure to act on backwardation (which was subsequently remedied by Ofgem) would lead to it exiting the market indicates the strength of its feeling (and its determination to signal the strength of its opposition). It does somewhat undermine the assurances that Octopus is committed to the GB retail market, however, this could have been a negotiating stance rather than a serious expression of intent.

While several suppliers remain strongly committed to market-wide CCB ringfencing, it seems likely that Octopus would continue to strongly object, although I would be surprised to see it shut up shop as a result. In any case, a second U-turn on the subject is not expected.

A deeply flawed consultation process with attempts to avoid statutory obligations

Several suppliers objected to the conduct of Ofgem’s November consultation. This was a Statutory Consultation, which is typically the final step before a regulatory change is made, however Ofgem introduced a large number of concepts which were not contained in previous policy consultations such as the July consultation, and also decided to bring forward guidelines which would be mandatory.

“Ofgem has at this last stage of statutory consultation, normally reserved for refining previously consulted-on policy proposals, introduced significant additional reporting requirements on suppliers, none of which has had any policy consultation prior to this statutory consultation stage. It is not usual process for Ofgem to introduce completely new policy proposals at the statutory consultation stage, and we consider that such an approach is particularly unreasonable given the volume of those proposals and the significant consequences for both market participants and consumers which are likely to flow from their implementation,”

– ScottishPower

ScottishPower pointed out that the volume of material to be reviewed was significant: (100-page consultation, 35 pages of guidance, 77 page impact assessment, alongside almost 25 pages of new licence conditions for each of gas and electricity) and the timescale for review was very short and coincided both with Christmas period (responses were due on 3 January), a number of other regulatory responses, and its year end accounting process (which was true for several other suppliers as well).

Energy UK also criticised Ofgem for only allowing suppliers to short a period to respond, given the many other new mechanisms such as the Government support schemes with which they were required to engage at the time. It also expressed concerns about the information burdens facing suppliers, and urged Ofgem to ensure it is adequately resourced to manage its monitoring obligations.

Centrica pointed out that Ofgem only published the Guidelines for the Financial Responsibility Principle, part way through the consultation despite the fact they were heavily referenced in the proposed licence conditions. This meant stakeholders had insufficient time to review them. Centrica also pointed out that the guidance was described as mandatory with breaches being treated the same as breaches of licence conditions, and therefore subject to potential compliance/enforcement action.

On this basis, Centrica said that the issuance of the guidance and any changes to it must be subject to the same consultation requirements as changes to the electricity and gas licences under the Electricity Act 1989 and Gas Act 1986, that is a 28-day minimum consultation period.

“These statutory procedural protections should be adhered to. Suppliers particularly need adequate time to understand, consider and respond. Ofgem have [sic] not demonstrated that deviating from a 28 day minimum consultation procedure is necessary here or would be procedurally fair,”

– Centrica

It went on to say that “guidance” is usually voluntary and indicates how to demonstrate compliance with actual obligations/legal requirements. It asked why mandatory obligations were not added directly to the licence saying Ofgem should demonstrate that mandatory guidance is necessary and that the mandatory obligations cannot be met through amended licence conditions, as would normally be expected. It also asked Ofgem to explain how it is using its legislative powers to require mandatory guidance, and in what case a rule change could be implemented through changes to the guidance and not through the licence, giving clear examples, why this process is being followed and how it differs from the current process whereby each change to a licence condition may be appealed to the CMA. Changes to guidance can usually be made with only 10 working days’ notice during which suppliers may make representations.

ScottishPower went further and accused Ofgem of deliberately trying to circumvent its consultation obligations under the Electricity Act 1989:

“While we accept that there is material that is not proportionate for inclusion in the licence conditions, we are also concerned that Ofgem is in this case circumventing the statutory protections under the 1989 Act modification regime by inserting key elements of the proposals (and prescriptive rules) into guidance with which suppliers are obliged to comply…By contrast, changes to licence conditions are generally subject to much greater scrutiny though the statutory consultation process, and importantly, give rise to a right of appeal to the CMA. This framework provides an important level of protection for licensees (and their investors). Ofgem should place such enforceable regulatory obligations, and other key elements of the relevant provisions, in the licence not in guidance,”

– ScottishPower

Ofgem has now confirmed that the guidance will not be mandatory, but it should never have attempted to introduce “mandatory guidance” in the first place – even the phrase should be a clue since “guidelines” are by definition advisory and not prescriptive, as we all understood during covid following well publicised problems with the police attempting to enforce guidance and being knocked back by the courts.

Stakeholders also complained that there was a lack of clarity and some duplication with other reporting obligations, something Ofgem recognised this time around saying “we therefore looked at our reporting and monitoring in the round to ensure that our requirements are proportionate and add value.” I’m sure many suppliers wondered why Ofgem had not done this at the outset – a frequent complaint among suppliers is the high burden placed on them by Ofgem’s information requests.

“We are concerned however, that Ofgem appears to have missed a number of steps in implementing its new prudential-style regulatory regime. It is being implemented from the bottom-up, with several specific and distinct regulatory tools with varying degrees of effectiveness. Ofgem needs to develop an overall vision for this new regulatory model and a framework to articulate how each component fits with the others, and how they work alongside existing regulation. We are already seeing evidence of disjointed and overlapping regulations, RFIs and other requirements which are a symptom of not having this in place,”

– E.On

Digesting and responding to consultations is time consuming – Ofgem should consider how every one of its proposals fits into the existing regulatory framework as a matter of course and not just in response to supplier complaints. It also must ensure that adequate time is given for suppliers to respond otherwise the quality of responses will be compromised, risking sub-standard regulations at the end of the process.

Key questions remain about profitability and investability

Several respondents to the November consultation expressed concerns about the inability of suppliers to earn profits and the consequent impact on attracting investment, something that would make raising additional capital challenging. Utilita pointed out that the alternative to raising capital is the use of retained profits, but at the 1.9% profitability allowed under the price cap, the minimum capital considered in the November consultation would take between 5 and 10 years to accrue based on the historic average annual dual fuel price of £1,100 per household.

“In all our correspondence and meetings with Ofgem since the introduction of the price cap Utilita have repeatedly informed Ofgem that the price cap was inadequate and predicted the failure of suppliers. We have also shared specific details of the losses that Utilita has made over the years due to errors in the price cap which has reduced our resilience, we have also informed Ofgem that continued policy failings have made the Supply sector a higher risk with limited returns and therefore less investable which all culminate in the risk of suppliers not being able to meet the obligation as it is currently proposed,”

– Utilita

E.On pointed out that Ofgem’s assumptions about supplier profitability are flawed – it asserts that the notional supplier on which it bases its models can recover its costs under the price cap, despite noting that the “vast majority” of real suppliers losing money over the past three years. This suggests that Ofgem’s idea of a notional supplier is too idealised, and either it does not reflect the true costs faced by the industry or the frictions between this hypothetical supplier and real suppliers are not adequately modelled.

“Ofgem’s assumptions about the notional supplier are flawed…Ofgem states an assumption that the notional supplier “is sufficiently efficient to recover its costs under the cap over a projected two-year period.” Ofgem recognises in the EBIT consultation that the vast majority of suppliers have been loss making over the last three years. This clearly shows that suppliers are not able to recover their costs under the cap so Ofgem should not assume that the notional supplier can do something that real suppliers can’t,”

– E.On

E.On also noted that Ofgem’s reporting requirements were so large that they now require specific resourcing, the costs of which should be recognised under the price cap. EDF related the issue of low market profitability with the lack of interest in the sector from investors, which is a problem both for business as usual and the need some suppliers will have for raising additional capital to comply with the proposed regulations.

“In the current market where the current price cap methodology prevents efficient suppliers from making a fair margin it is not clear why any investor would provide additional funding or other financial instruments for a retail supplier to meet the capital adequacy requirements as currently proposed. Unless investors can see a route to making a fair margin then there is no clear business case for the provision of such additional financial support. With this in mind, it is important Ofgem also carefully considers the interlinkages with its concurrent consultation on changes to the EBIT allowance in the Default Tariff Cap (DTC), which could further reduce a supplier’s ability to achieve a fair margin, only serving to further reduce suppliers’ investability,”

– EDF

In November, Ofgem launched a further consultation on amendments to the EBIT allowance in the price cap, and is currently considering the responses (a statutory consultation was expected in February but this has not yet been launched). In the introduction to the November EBIT consultation, Ofgem noted that responses to its EBIT policy consultation in August had “expressed the need for more time to consider proposed changes” and “concerns with the pace of our approach”, with “multiple respondents noting the complexity of areas being considered”.

Indeed, among the non-confidential responses to the August consultation are several bad tempered remarks from suppliers around the volume of work and the fact Ofgem was pressuring them for detailed analyses it could arguably produce itself from their published accounts. EDF noted “it is disappointing that such a fundamental topic is being rushed through without providing sufficient time to enable suppliers to engage meaningfully”, and went on to say it had insufficient time to develop a proper response, which “undermines any confidence with regards the rigour of Ofgem’s approach”.

Ofgem clearly did not listen since it launched the new consultation in parallel with the financial resilience consultation and at the same time as suppliers were implementing the various Government support schemes, however it did at least make this a further policy consultation instead of the initially intended statutory consultation.

Some suppliers challenged the notion that they have been making excessive profits, describing the market as having been loss-making for a significant period, and unsustainable. Other suppliers said Ofgem had ignored periods where suppliers were loss making, and was only focussing now on the EBIT allowance as some level of profitability had returned. However, consumer advocates and consumers were of the opinion that the current EBIT allowance is too generous and expressed the need to review the EBIT allowance promptly.

“For Ofgem to raise a consultation of this type as soon as the value of returns increases to a positive value after so many years of suppliers facing negative returns reflects poorly on the quality of regulation provided to the industry by Ofgem. The proposed way forward shows clearly the neglectful approach to healthy competition displayed by Ofgem, placing as it does short term regulatory cost cutting at the expense of long-term market resilience and stability,”

– Utilita, response to August EBIT consultation

Suppliers also challenged Ofgem’s approach to technical changes to the EBIT allowance without considering the overall risk and cost landscape for suppliers, which have been generally loss-making since the inception of the price cap. Octopus in particular urged to conduct a more strategic review of retail regulation involving a wider review of the price cap methodology.

“In reality high systematic risk also means that, whatever the EBIT margin, gaining access to capital is becoming increasingly difficult for the sector… there is a risk that this situation is creating financial strain on some other retailers and holding up much needed investment for net zero in the sector as a whole. Against this backdrop in particular, it is worrying that Ofgem’s document – and subsequent communications – suggest that the current EBIT allowance is providing an upside to suppliers, and may need to be revised downwards. Contrary to Ofgem’s indications, we see little evidence that a balanced, evidence based review of the EBIT allowance would do anything other than increase the allowance and the level of the cap. We find it strange that Ofgem appears to want to move at pace to conduct and complete this review,”

– Octopus Energy, response to August EBIT consultation

Of course, consumers would like to pay less for energy (and everything else) but that does not mean they should, or that supplier profitability should be reduced. Energy supply has clearly been loss-making for many suppliers – half of them exited in late 2021 – and there has been a dramatic reduction in market entry. The lack of innovation in the sector can also be linked directly with low levels of profitability and low investor interest.

Ofgem says it has not yet formed a view on whether the existing allowance over or under estimates a “normal profit” in the retail market but recognises that market conditions and risks have changed significantly since the EBIT methodology and level was first set in 2019. It also recognises that many suppliers have become insolvent in the past year and analysis which highlights the negative profit margins in real supply businesses, even before the “extraordinary” increases in wholesale cost. It seems that Ofgem is struggling to abandon the view that suppliers are profiteering, despite firm evidence to the contrary – the high level of cost faced by consumers is not in itself proof that suppliers are earning excess profits, or indeed any profits at all.

Arguably, Ofgem has also mis-characterised the responses to the August EBIT consultation, particularly around the use of the Capital Asset Pricing Model (“CAPM”). Of the 14 responses to the consultation, seven were made public. Of these, ScottishPower, Octopus Energy and Utilita all objected to the use of CAPM for assessing the cost of capital for energy suppliers while in the November consultation, Ofgem implied only one supplier had been against it. All three of these made similar points about the suitability of CAPM for asset-light retail businesses versus the more typical application in regulated networks. I don’t propose to discuss this further here – Ofgem has clearly deviated again from its planned approach since the February consultation did not materialise. However, this does raise further questions about the quality of Ofgem’s consultations – responses should be accurately reflected in its documentation.

Ongoing need for fundamental market reform

All of this highlights the need for a more fundamental reform of the market, and the approach to regulation. While I support measures to improve financial resilience, and would support ringfencing of consumer credit balances, I have concerns around the implementation of the capital adequacy regime. There are reasons to doubt the effectiveness of both the self-reporting principle, and Ofgem’s ability to properly analyse the data it receives.

More broadly, the issue of low profitability needs to be addressed. The delayed progress in the EBIT allowance reform is positive given strong market push-back in the initial pace of the proposed changes, but Ofgem needs to get its head around the basic fact that the industry is insufficiently profitable to support innovation, and that the lack of innovation is likely to inhibit progress towards net zero.

It is also important for Ofgem to improve its market engagement. Ofgem continues to treat suppliers with hostility and encourages the public to view suppliers negatively through the language it uses when discussing supply-related matters. The use of terms such as “clamping down” are not constructive and should be discouraged. Ofgem, and the Government need to take a less combative and more collaborative tone with suppliers if consumer trust is to be restored.

Part of this relates to the conduct of consultations, which also appears to be punitive. Ofgem is bombarding suppliers with both information requests and high volumes of often poorly constructed consultations, which can lack the necessary detail for suppliers to give a comprehensive response. Ofgem has clearly been stung by the widespread criticisms it faced in the past year, but that does not excuse its current highly reactive and rather aggressive treatment of suppliers. Good regulation relies on good quality engagement from stakeholders on potential changes – this is not achieved when consultations are rushed, and overlap. Attempting to circumvent statutory consultation process by implementing mandatory market change outside the gas and electricity licences was particularly egregious.

Of course, I continue to prefer the Financial Conduct Authority to take over this part of the energy sector. I would have a good deal more confidence in the ability of the FCA to interpret the financial data submitted by suppliers under the enhanced Financial Responsibility Principle. I would also have more confidence in the ability of the FCA to properly calculate the cost of capital and other metrics important in the determination of the price cap as these are fundamentally rooted in finance and not energy. Questions about the different impact on net assets of marking hedges to market versus hedge accounting should be far easier for the FCA to address.

Much of the dysfunction in the market can be placed at Ofgem’s door either directly through its regulatory approach or indirectly, by failing to properly advise the government about the detrimental effects of certain policy decisions such as the price cap. It’s time for real change.

Original article l KeyFacts Energy Industry Directory: Watt-Logic

KEYFACT Energy

KEYFACT Energy