By Kathryn Porter, Watt-Logic

In May last year, the UK Government introduced a windfall tax on the profits of oil and gas companies operating on the UK Continental Shelf (“UKCS”), in response to press stories about “excess” energy company profits. Regular readers will know my feelings about this tax, and its subsequent increase in November: I said it was likely to dis-incentivise much-needed investment in domestic production, and I objected on the basis of fairness: oil and gas companies do not receive subsidies or rebates in years when prices are low, and are not compensated when they drill dry wells. There is evidence that my prediction of reduced UKCS activity is coming to pass which is bad news for energy security, consumer’s pockets and the Treasury.

What is the oil and gas windfall tax?

The Energy (Oil and Gas) Profits Levy Act 2022 received Royal Assent on 14 July 2022. The Energy Profits Levy (“EPL”), applies in addition to the Ring Fence Corporation Tax (“RFCT”) of 30% and the Supplementary Charge to Corporation Tax (“SCT”) at a further 10% paid by oil and gas companies instead of regular corporation tax, however, certain losses and costs such as de-commissioning costs are tax deductible. The original EPL had the following features:

- An initial rate of 25% which takes the headline rate of taxation for oil and gas companies to 65%. The rate would be tapered down if prices reverted to historic levels;

- Applied to profits arising on or after 26 May 2022;

- Included a deduction of up to 80% for qualifying expenditure including capital and leasing expenditure, and operating expenditure that improves oil or gas recovery or increases tariff receipts and is not routine repair and maintenance;

- No deductions for financing and de-commissioning costs;

- Losses generated under this Levy could be surrendered to group companies for utilisation against their Levy profits, however RFCT and SCT losses cannot be used to reduce Levy profits;

- No adjustments for commodity hedges which follow the same treatment as for RFCT.

- The Levy was expected to raise £5 billion in its first year. The investment allowance meant that companies could reduce their exposure by making investments that increase UK oil and gas production. It was due to expire by December 2025, however, in the November Autumn Statement, the EPL rate was increased from 25% to 35% from January 2023 and extended 31 March 2028. The investment allowance was reduced to 29% with the 80% allowance being maintained for expenditures relating to decarbonisation of oil and gas production only.

Companies pull back from the UKCS as a result of the windfall tax

Harbour Energy, the largest producer in the UK North Sea has seen its profits “all but wiped out” by the windfall tax, and has already paid US$ 205 million to the Treasury as a result of the levy. Profit after tax fell to US$ 8 million in 2022 from US$ 101 million the previous year, despite higher oil and gas prices and production growing by almost a fifth. The company said the windfall tax had resulted in a US$ 1.5 billion “one-off non-cash deferred tax charge”, and has announced job losses in its North Sea operations as and plans shift its expansion outside the UK as a result.

“The UK energy profits levy, which applies irrespective of actual or realised commodity prices, has disproportionately impacted the UK-focused independent oil and gas companies that are critical for domestic energy security. For Harbour, the UK’s largest oil and gas producer, it has all but wiped out our profit for the year. This has driven us to reduce our UK investment and staffing levels. Given the fiscal instability and outlook for investment in the country, it has also reinforced our strategic goal to grow and diversify internationally,”

– Linda Cook, chief executive of Harbour Energy

Operators of all sizes have criticised the tax with TotalEnergies, Equinor, Shell and EnQuest, among others, all revealing plans to reduce UK spending this year, while credit rating agency Moody’s points out that the three largest European integrated oil and gas companies it rates — BP, Shell and TotalEnergies will “be hurt” by the tax, but that their scale, global and downstream diversification will limit the financial effects. It said the increased windfall tax will “crimp the North Sea producers’ free cash flow generation”, particularly in the case of smaller and UK-focused E&P firms.

“The UK oil and gas industry experienced significant fiscal instability with the introduction and subsequent revision of the Energy Profit Levy in 2022. In its revised form, the Energy Profit Levy, and the fiscal uncertainty it has created, brings material and negative unintended consequences for financing capacity, JV (joint venture) partner alignment, and the free cash flow generation required to support continued investment. We continue to look towards the UK government to create an economic environment that encourages investment in the UK North Sea,”

– Gilad Myerson, executive chairman Ithaca Energy

The final investment decisions for Ithaca’s Cambo and Rosebank fields, the largest undeveloped fields in the UK North Sea, had been expected in the first half of this year but this timeline is now in doubt, due less favourable conditions for financing. Ithaca CEO Gilad Meyerson has noted that credit availability has fallen significantly. Reserves-based lending models typically assume an oil price of US$ 50-US$ 54 /barrel – once a 75% tax rate is added, there is very little credit availability to develop projects.

Similarly EnQuest, another UK independent, has described the UK as being “fiscally unstable”.

“The U.K. is particularly unstable fiscally, which I think affects the long-term views on investments. You can do short-cycle investments but long-cycle investments are difficult in a very volatile (environment). There’s a lot of public pressure to tax oil companies with high profits, even though the profits are not being made in the U.K. — for example, [for] many of the majors, it’s maybe 5% now in terms of their net income in the UK,”

– Amjad Bseisu, CEO EnQuest

Trade body Offshore Energies UK (“OEUK”), has warned that the tax, if continued, will increase the need for fossil fuel imports and harm efforts to hit net-zero targets. It suggested more than 90% of companies involved in exploration and production on the UKCS have cut their spending, with concerns over further political disruption, including a possible Labour government adding further taxes contributing to the negative outlook.

Windfall tax will accelerate the decline in UKCS production…

In its annual Business Outlook report, OEUK said projects equivalent to a year’s North Sea supply – about 500 million barrels of oil – had been stalled or shelved during 2022, with imports costing the country £117 billion in 2022, compared with £54 billion the previous year. Its forecasts suggest that the UK will be need to import 85% of the oil and gas it needs within a decade, compared with less than half at the moment.

“The reality is that to keep the lights on and grow our economy, we need both. By the mid-2030s, according to the Climate Change Committee, oil and gas will still provide half our energy needs. We should be aiming to get as much as possible of that energy from our own resources, meaning the North Sea. That makes it essential for the UK to attract investment. The alternative is to become ever more reliant on other countries. Without investment we risk having to import not just our day-to-day energy but also the kit and expertise needed to reach net zero,”

– Ross Dornan, market intelligence manager, Offshore Energies UK

Only three new fields gained development approval last year (Jackdaw, Abigail and Tommeliten A which is mainly in Norwegian waters, but extends slightly across the UK boundary; and the eastern extension to the existing Tolmount field). These projects contain just over 80 million boe of reserves (equivalent to around 2 months of output at current rates) for around £1 billion in capital investment. This is similar to the last three years, but is significantly lower than the average in the previous decade of almost 450 million boe per year.

There are 10 projects undergoing final regulatory scrutiny which together could contain 650 million boe of new reserves and consume up to £8 billion of development capital, however on average these fields were discovered 33 years ago. The lack of new approvals is negatively affecting drilling activity, which is now only around one quarter of the rate of well de-commissioning. Only 55 new wells (46 development, 5 exploration and 4 appraisal) started drilling in 2022 – the lowest rate since 1970 and 60% lower than in 2019.

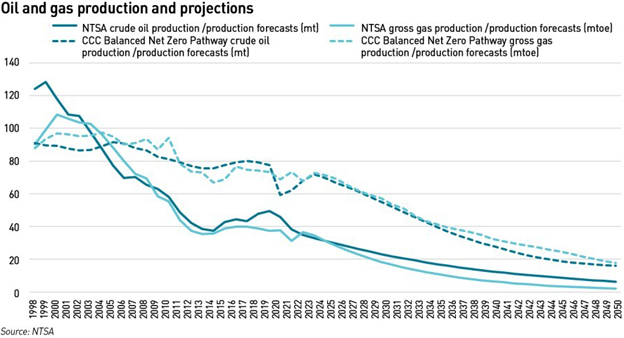

Current projections from the North Sea Transition Authority (“NSTA”) suggest that the UK’s oil and gas production will more than halve over the course of this decade, with crude oil output dropping from 49.34 million tonnes in 2019 to 24.62 mt in 2028, and natural gas production falling from 37.51 mtoe to 20.49 mtoe over the same period. Capital expenditure is forecast to fall from £5.42 billion to £2.5 billion over the decade, with de-comissioning costs rising from £1.39 billion to £2.0 billion. Even when compared with the Committee on Climate Change’s predictions for a dramatic reduction in oil and gas demand to 2050, these figures are very concerning.

Research from Westwood Global Energy suggests the tax changes could accelerate the mass departure of rigs from the North Sea, which is already in “full swing” while some planned greenfield projects, may struggle to reach their final investment decision (“FID”) due to the increased levy. North Sea total rig supply has continued to fall since 2017 and is now 40% lower than in March 2017. In the past two years alone, 13 rigs have left the region – either for work elsewhere or through retirement – and two more are already confirmed for relocation later this year to Canada and Namibia.

There is concern that once rigs exit the region, they may not return given high mobilisation costs and attractive contract terms and day-rates elsewhere, particularly the Golden Triangle (US Gulf of Mexico, South America and West Africa), the Middle East or Australasia. This could mean a smaller pool of rigs within the North Sea, leading to less choice and higher day-rates for those operators that do wish to continue drilling in the next few years.

The North Sea Chapter of the International Association of Drilling Contractors recently sent a letter to 650 UK MPs and 129 MSPs warning that further harsh-environment rigs could be “lost for good” due to the windfall tax changes. It pointed out that rigs are not only necessary for new projects, they are also vital for de-commissioning expired wells, and would be needed in any carbon storage projects in the North Sea.

Not only is the retirement and re-location of rigs concerning, but there is almost no new rig and vessel-building going on globally at the moment. Traditionally, these assets were financed by industrial companies and specialist financing groups via their own balance sheets rather than by private equity or investor groups. The rig and vessel sectors remain highly leveraged from previous downturns, and it is difficult to predict the long-term demand outlook for these capital-intensive assets.

It is important that we don’t lose track of important enabling infrastructure to ensure we are able to optimise our domestic oil and gas resources.

…despite a clear ongoing need for hydrocarbons despite net zero

The Climate Change Committee (“CCC”) expects that half the UK’s energy requirements between now and 2050 will be met by oil and gas, and as much as 64% of UK energy needs between 2022 and 2037. If domestic production continues to decline, this will require an increase in imports. It also ignores the fact that hydrocarbons are used as feedstocks for a large number of industrial processes. Mark Lappin, member of Brindex, the UK association for independent North Sea operators, blames the instability of the UK’s investment regime for the further downgrades in production.

“A lot of our industry is about long-term planning for exploration and production. If you can’t plan for your investment over the long term, because a jurisdiction changes things along the way – that’s something that you’d factor into your investment. We need a state of stability and we need to be able to plan for our projects and if the tax levels are particularly high, that will clearly affect investment,”

– Mark Lappin, member of Brindex

Net zero pathways from both the CCC and International Energy Authority (“IEA”) suggest that global energy demand will fall. This feels a lot like back-solving to get the desired answer…with many countries still industrialising, reductions in total demand occurring throughout the period to 2050 seem unlikely. A more realistic outlook is presented by consulting form McKinsey which sees global energy demand growing by 50% to 2050, while fossil fuel demand peaks this decade, possibly 2023-2025, before declining significantly.

What is interesting in this chart is that the volumes of oil and gas required in the years to 2050 are lower, but not materially so, than the volumes required between 2000 to now. This means that we should not be complacent about the production of hydrocarbons (which have other significant uses beyond energy) – assuming that oil and gas use will decline to irrelevance by 2050 is completely incorrect, but there is a sense that policymakers believe this in their casual attitude towards hydrocarbon production. It is also something which seems to be escaping the attention of investors who have shied away from funding the projects needed to keep hydrocarbon costs within reasonable bounds.

“The UK urgently needs energy security and drivers of economic value. We can produce some of the lowest carbon oil and gas in the world, on our doorstep in the North Sea. Why should we damage this industry, only to import more from international markets? That seems to me to be a completely illogical path and one that is a major negative, not a positive, in our stated path to net-zero. The stark reality is the energy transition won’t happen in the next decade. Oil and gas will still be a meaningful contributor to meeting global energy demand for the next 30-40 years and will require long-term financing…However, the UK is a mature basin, with high operating costs, and tax rates do really influence investment decisions. The industry deserves support and needs certainty within the fiscal regime,”

– Mike Beveridge, vice-chairman, energy and power investment at Piper Sandler

Clearly, we need to keep exploiting North Sea oil and gas resources, but there could be significantly more projects demanding capital than there is capital available from investors, with the windfall tax acting as a major stumbling block due to its excessive tax burden and fiscal uncertainty.

Norway again is leading the way

Norway continues to be ahead of the energy curve, although there are some risks of policy self-harm there too, arising from electrification and a new interest in wind power. However, Norway continues to develop its North Sea assets and infrastructure, recognising that hydrocarbons will be needed for several decades to come. The country is determined to capitalise on global energy prices and energy security concerns by maximising production.

Last year, Norway saw a record number of FIDs, stimulated by fiscal regime incentives exact opposite of what is happening in the UK. These will deliver 2.5 billion boe and over US$ 40 billion of investment. According to WoodMackenzie there are 50 new projects in development in Norway, which is the same number of new fields approved in the UK over the last 10 years.

“We constantly need new discoveries to further develop the Norwegian Continental Shelf. Facilitating new discoveries in the north is important both for Europe, the country and the region,”

– Terje Aasland, Norwegian Minister for Petroleum and Energy

Norway is currently re-considering new pipeline infrastructure for exporting gas from the Barents Sea, to supplement the current LNG export routes via Hammerfest. The country is actively looking for new production sites in the region – the 2023 licensing round includes 92 more northerly blocks, comprising 78 blocks in the Barents Sea and 14 blocks in the Norwegian Sea. Exploration activity in the Barents Sea continues to deliver promising finds providing the necessary market infrastructure can be secured.

A knee-jerk reaction based on flawed assumptions

Headline-grabbing “excess” profits were largely earned by oil and gas majors – large multi-national operators with assets round the globe. However, in recent years, these companies reduced their North Sea activities, being replaced by smaller, specialist operators such as Harbour Energy and Ithaca Energy. In addition, large companies such as Shell and BP have accumulated tax losses in the UKCS due to de-commissioning activities, meaning the windfall tax is having a lower impact on them.

“Harbour Energy earns record profits” is unlikely to attract much public interest, yet the company is now the largest producer on the UKCS.

The Government needs to urgently re-assess this windfall tax – at the very least it should reverse the extension to the tax announced in the Autumn Statement – restoring the tax-deduction for new E&P investments in the UKCS would align the need to boost domestic production with the desire to increase tax revenues, but more broadly, the Government should avoid being bounced into harmful policy decisions by ill-informed public reactions.

The Government should also explain clearly to both the public and the investment community why we need to keep developing North Sea assets – protest groups such as Just Stop Oil like to claim that North Sea oil and gas is no longer needed because of net zero, but even on the CCC’s ambitious net zero pathway, it is clearly the case that significant volumes of hydrocarbons will be required between now and 2050. The only alternative to domestic production is to increase imports, which immediately increases emissions due to transportation, and means we lose control over production emissions.

More broadly, governments and the investor community need to recognise that scarcity increases prices – we are not going to stop needing hydrocarbons in the coming decades even for energy, never mind for plastics, fertilisers and all the other things made from these raw materials, so if we fail to invest in new production, the inevitable outcome will be higher prices, and less energy security both of which lead to hardship. Instead of taxing UKCS production out of existence, the Government needs to change course and provide incentives to new E&P activity, recognising that the region is more technically challenging to exploit than other areas of the world.

ESG-minded investors should be keen to avoid hardship and should recognise that supporting projects which utilise existing infrastructure such as in the North Sea is more environmentally conscious than the alternatives. They should also recognise that at the moment, the alternative to hydrocarbons in many cases is actually hardship as was illustrated very clearly in Sri Lanka last year where economic collapse was in part caused by the drastic fall in agricultural yields when the country experimented with banning synthetic fertilisers, a ban which has subsequently been lifted.

It is essential that energy policy is based on realism, and that investors are encouraged to support important and necessary projects without being spooked by the word “fossil” in front of “fuel”. It is also important that the industry presents a more compelling case to investors – historically oil and gas projects sold themselves if the economics lined up and the field development plans were credible: no-one questioned the market need for oil and gas. We need to remind investors that despite net zero, that market need will persist, requiring the replacement of depleted assets.

The current economic downturn has re-focused investors’ minds on returns above ESG. Expensive energy is always linked to economic decline, something investors and lenders should keep in mind when new oil and gas projects cross their desks.

Original article l KeyFacts Energy Industry Directory: Watt-Logic

KEYFACT Energy

KEYFACT Energy