Dave Waters, Director & Geoscience Consultant, Paetoro Consulting UK Ltd

Many react to undue "doomism" that isn't based in observation. That's understandable, and is always relevant to climate change discussion. That said, there are certain trends that are anticipated, and clear. The precise timing and magnitude of events is harder but that does not preclude observation of a trend that matters.

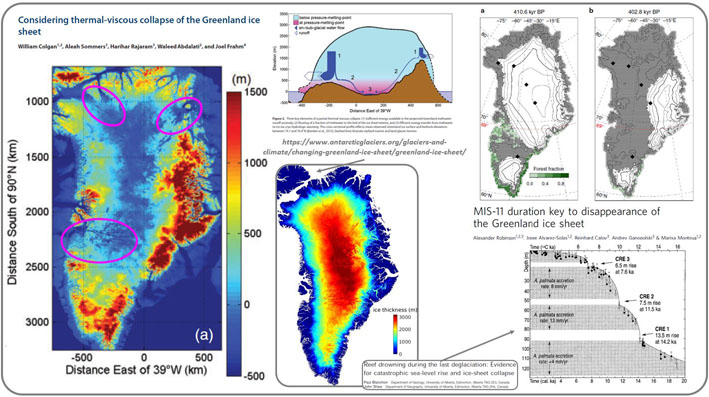

Without dwelling on what proportion of climate change is anthropogenic and otherwise - that is not the topic of this post - it is clear that one significant trend is the vulnerability of the Greenland ice sheet.

Not least because it largely disappeared in an interglacial just over 400 ka ago, so we know it is vulnerable. It is on course to essentially go again. The real question is when and how quickly, and that is subject to many uncertain variables. We can argue over and over about what past disappearance means for current warming, but the point is we are heading into a similar temperature space, and 400 ka ago, we didn't have a third of a global population of 8 billion living in coastal areas.

That doesn't mean the end of the word is nigh, but it could mean the end of geographies and habitats as we know them.

Chances are it will take millennia to change, but there are also hints from coral reef observations during the last deglaciations, that much faster metre/decade scale events occurred - probably related to large sub-glacial mega-flooding events.

One study is always just one study, but it is not counter intuitive that such things can occur. North America and Eurasia are resplendent with evidence for such events during past deglaciations. Heavy ice can act as a big dam for subglacial lakes, until...

A key feature of the Greenland ice sheet is both how thick it is - up to 3 km, but also how much of it rests on land that is below sea level. For the most part given the thickness and weight of ice that might seem academic, but the pressures and geothermal gradients take that ice to near melting point at the base, and that influences the lubrication and speed of calving.

The worry is always the "ripping up the lino" scenario, where incursions of sea water from the fringe further exacerbate this effect. In the figure, three particularly vulnerable areas highlight where the current sea and associated deep glacial fjords have access into the sub-sea level interior. These are logical pathways for any instability that might occur in the future. Landbound ice does not have to melt to raise sea level, it just has to change from being landborne to seaborne.

The other cause for concern of course is the strong driver for the global ocean conveyor circulation that is strongly influenced by ice melt off SE Greenland.

While any changes are likely to occur over millennia, albeit likely punctuated with occasional mega-flood events - the eventual sea level rise at stake is of the order 5-7m.

Amidst efforts to halt anthropogenic change, there is also need to prepare for that which many now be inevitable.

KeyFacts Energy Industry Directory: Paetoro Consulting

KEYFACT Energy

KEYFACT Energy