By Kathryn Porter, Watt-Logic

The pervasive narratives about off-shore wind in recent years have been that costs are falling, and that wind power is cheap. But as I noted in a previous blog, and in my latest article for The Telegraph, things are not quite so rosy as wind turbine manufacturers have been losing money hand over fist in recent years. Collectively over the past five years the top four listed turbine producers outside China have lost almost US$ 7 billion – and over US$ 5 billion last year alone. Last year the chief executive of turbine-maker Vestas said that the company lost 8% on every turbine sold.

But OEMs are not the only ones feeling the pain. Developers are struggling to make the numbers add up, leading to failing off-shore wind tenders, PPA re-negotiations, and project cancellations. While policy-makers set ever more ambitious off-shore wind targets, they have never looked less likely to be met,

Warranty issues drive turbine losses…

Some of the OEM losses are down to warranty issues – this means the turbines have not performed as expected requiring the manufacturers to compensate windfarm developers and rectify problems. Back in June, Siemens warned that components in wind turbines made by its subsidiary Siemens Gamesa are wearing out faster than expected. The problem appears to involve critical parts such as bearings and blades, and is affecting both newly installed and older turbines in up to 15% – 30% of the installed on-shore fleet.

Management believes the cost of remediation could exceed €1 billion, effectively wiping out more than a third of the profit the company is expected to make doing maintenance on wind turbines it already installed. This has led to speculation – denied by the company – that it has suspended sales of on-shore turbines until the problems are resolved. There are further reports the company may close factories in order to stem losses.

Siemens is also finding problems with its off-shore turbines, which are failing to meet productivity targets due to rising material costs and manufacturing delays. Privately this is attributed to the pressure for ever larger turbines which are harder to get right.

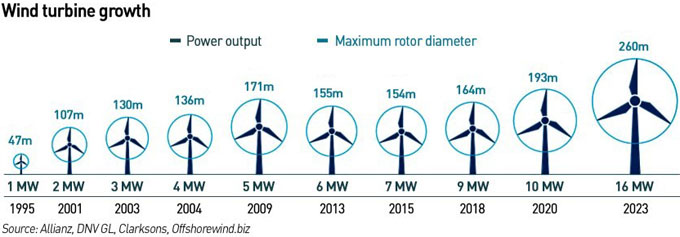

“We are quite used to wind turbines with capacities of 8 MW or 9 MW, but now we’re seeing newer models reaching 14 MW to 18 MW. A project in Australia is even planning to use 20 MW turbines. Inevitably, with the increase in size comes a corresponding increase in risk. Although turbines are engineered to work within certain conditions, there is a lack of real-world data on both performance and the long-term impacts on these larger turbines and their associated infrastructure, especially cables and their maintenance requirements,”

– Dr Wei Zhang, senior risk consultant, natural resources construction at Allianz Commercial

Wind turbines and their blades have rapidly been increasing. The largest turbines are in China (16 MW) but outside of China, the largest as of June 2023 were the 15 MW Vestas units at the He Dreiht and Baltic Power projects in Germany and Poland respectively. These units are still prototypes with the projects not due to begin commercial operations until next year. The largest turbines currently in operation are the 13 MW GE turbines at Dogger Bank in the UK.

Behavioural software has been used to enable larger turbines to be used without a corresponding increase in expensive steel and concrete by allowing them to engage automatic protection measures under different weather conditions. But the bigger turbines become, the more susceptible they are to faults. Larger sizes combined with pressure for speedy delivery, created the conditions for breakages. Insiders now suggest that the growth in capacity per turbine has now peaked, at least for the time being in European projects.

“Physics inherently punishes larger turbines. Larger blades will inherently deflect more, which means they need stiffer spar caps, shear webs and more expensive materials. They will also weigh more which pushes more stress and strain through the blade, root and nacelle during each rotation,”

– Rob West, analyst at consultancy Thunder Said Energy

Interestingly, a major cause of insurance claims relating to off-shore wind is attributed to cabling – while subsea power cables represent about 10% of a wind farm’s overall costs, cable failures account for about 80% of the payouts for off-shore wind insurance claims according to AXA. Rival Allianz says 53% of off-shore wind claims by value over the past six years have related to cable damages across Central and Eastern Europe and Germany. This includes loss of an entire cable during transport and cables being bent beyond repair during installation.

“The push to rapidly develop more powerful machines is piling pressure on manufacturers, the supply chain and the insurance market. Scaling up is creating growing financial risks that pose a fundamental threat to the sector,”

– Fraser McLachlan, CEO of GCube Insurance

A report from GCube Insurance, a member of the Tokio Marine HCC group of companies, has warned that the rapid scaling up of off-shore wind capacity may be creating unsustainable market risks. GCube Insurance is a leading underwriter for utility-scale renewable energy projects, and has compiled ten years of claims data, finding that there has been a “rising tide of claims” relating to mechanical breakdowns, component failures and serial defects. 55% of claims come from component failures during construction of 8 MW+ sized machines, within the first two years of operation.

Average offshore wind losses in claims dealt with by GCube Insurance rose from £1 million in 2012 to more than £7 million in 2021. The firm says that new insurers must take a more realistic approach to pricing and T&Cs, otherwise “substantial losses [could] exacerbate the current instability in off-shore wind markets”.

…but wider market economics don’t stack up

OEM losses have also been driven by pricing structures designed to win market share, and aggressive windfarm developers who have refused to pay up, often while pocketing billions in subsidies. The market has started to look, if not like a Ponzi scheme, then like a house of cards built on the shakiest of foundations. Turbine manufacturers are all busily re-negotiating contracts and insisting on better terms to stem their losses, otherwise they will simply shift to other, more profitable, activities. This in turn is putting pressure on developers who are now going cap in hand to governments, begging for more subsidies and more tax breaks, all of which must be paid for by tax-payers or bill-payers.

According to Fraser McLachlan, chief executive of GCube Insurance, participation in the off-shore wind market has become increasingly risky, not only for insurers, but also manufacturers, developers, and suppliers – with some now facing a material risk to their survival.

“The whole value chain is in trouble. The contracts signed for offshore [wind] will be heavily lossmaking for a long time until the different governments realise that they need to give $80-$100 per MWh and not $30-$40,”

– Renaud Saleur, CEO Anaconda Invest

The S&P Global Clean Energy Index, which is made up of 100 of the biggest companies in solar, wind power and other renewables-related businesses, has dropped 20.2% over the past two months, on course for its worst annual performance since 2013. By contrast, the oil and gas-heavy S&P 500 Energy Index has added 6%.

Contracts between turbine OEMs and project developers typically include inflation provisions, however, in the market environment these provisions do not fully compensate for the rise in raw input costs that turbine manufacturers incur. Manufacturers are therefore increasing prices and renegotiating contracts to manage financial risks, seeking to add new clauses to link the final wind turbine price to indices tracking input costs.

This in turn is forcing developers to renegotiate their contracts, as they also struggle to adjust to higher prices. At best these renegotiations delay projects and at worst they lead to their cancellation. Over the summer, the developers of four off-shore wind farms off the coast of New York with an expected capacity of 4.3 GW lobbied for enhanced economics from New York state, arguing that inflation, supply chain issues and drawn-out governmental approvals have made the projects financially difficult under the current contract terms. New York, has a goal to power its grid with 70% renewable energy by 2030.

To combat the growing threat from Chinese turbine makers, the EU is considering launching an investigation into China’s use of subsidies to promote the country’s wind turbine manufacturers, including Goldwind, Envision, Mingyang and Windey. The EU has already imposed tariffs on Chinese glass fibre fabrics, which are used in wind turbine blades. Chinese wind turbine manufacturers are starting to win orders in the EU, leading to warnings that the bloc’s wind industry could be “wiped out within the next year” if policymakers fail to act.

“Chinese wind equipment manufacturers have been implementing an aggressive strategy to enter European markets,”

– Thierry Breton, EU internal market commissioner

Acting EU competition commissioner, Didier Reynders has said that cheap Chinese imports could threated European businesses. A decision on whether to go ahead with an investigation is expected later this month, despite an angry reaction from Beijing over a similar probe into electric vehicles.

Off-shore wind tenders failing to deliver

These cost pressures are causing projects around the world to dry up. During the whole of 2022 there were no offshore wind investments in the EU other than a handful of small floating projects. Several projects had been expected to reach financial close last year, but final investment decisions were delayed due to inflation, market interventions, and uncertainty about future revenues. Overall, the EU saw only 9 GW worth of new turbine orders in 2022, a 47% drop on 2021.

Developers point to rising supply chain costs, but while these costs have indeed risen, they have simply deepened the losses faced by manufacturers. Those losses for the most part were already there before the Ukraine war triggered global price rises. The reason is that the sums for this market simply don’t add up: governments think they are subsidising an immature technology which will eventually be self-sustaining. But after a quarter of a century of subsidies, this market is no longer immature. It just won’t be economic until people realise that despite having operating costs which are close to zero, windfarms need to earn a lot of money to repay their very high capital costs, something policy-makers are reluctant to admit because it would mean abandoning the rhetoric of “cheap renewables”.

Windfarm tenders around the world are coming up short. Last month the latest round of the UK’s renewables subsidy programme saw no bids at all from off-shore wind developers, with only two projects from last year’s round moving ahead to construction. Leading developer, Vattenfall, stopped work on its Norfolk Boreas wind farm in July, citing rising costs. A recent tender in Germany was undersubscribed – despite the target volume having been close to halved during the process, it still came up short of capacity offered. This is by no mean the first disappointing German wind auction, with developers prefering the more commerically friendly auctions in the Netherlands.

Over in the United States, despite the support offered by the Inflation Reduction Act, windfarm projects are also struggling. Orsted, the global leader in off-shore wind, has indicated it may write off more than US$2 billion in costs tied to three US-based projects that have not yet begun construction. It may withdraw from these projects (Ocean Wind 2 off New Jersey, Revolution Wind off Connecticut and Rhode Island, and Sunrise Wind off New York) if it can’t find a way to make them economically viable.

In August, the US government held an auction for off-shore wind leases in the Gulf of Mexico which attracted almost no interest from developers. One company, RWE, made a bid for one of three lease areas and won due to a lack of competition. There were no bids on the other two lease areas. Analysts said companies were reluctant to bid because the states along the Gulf coast do not have requirements to buy electricity from offshore windfarms. Meanwhile, projects off New York are asking for an average 48% increase in guaranteed prices that could add US$ 880 billion per year to electricity prices.

Long-term power contracts for the electricity produced by offshore windfarms (known as Power Purchase Agreements or PPAs) have been cancelled, with windfarm developers paying exit penalties. Developer Avangrid, a subsidiary of Spanish giant Iberdrola, cancelled its contracts for output from the planned 804 MW Park City windfarm and the 1.2 GW Commonwealth Wind project. It plans to re-bid these projects in future auctions, but for now they have been terminated. Shell, Equinor and Orsted have all also sought to cancel or re-negotiate similar contracts, while the Ocean Winds-Shell project, SouthCoast Wind, agreed to pay US$ 60 million to cancel contracts with Massachusetts utilities.

Renewables targets at risk

All of this is putting renewables targets at risk. In the US, President Joe Biden wants to see 30 GW of off-shore wind by 2030, a target many analysts believe will simply not be met. Despite the incentives offered by the Inflation Reduction Act (“IRA”), offshore wind developers have said the IRA’s subsidies are insufficient for projects to thrive in the current environment, and are lobbying for additional concessions. The New York State Energy Research and Development Authority which is implementing the state’s offshore wind mandate of 9 GW by 2035 has warned that delays in deploying offshore wind could threaten state renewables targets and asked the New York State Department of Public Service to approve price increases to contracts with Equinor, BP and Orsted.

“Thirty gigawatts is now unfortunately not something that the developers are really aspiring to. We want to meet as high a gigawatt target as possible, but it’s not going to be possible to meet those 30 GW,”

– Michael Brown, US country manager for Ocean Winds

Over in North Carolina, Duke Energy has dropped offshore wind altogether from its latest long-term energy plan, favouring nuclear, solar, and onshore wind. Duke has also committed to only close existing power plants once replacements are in operation, hoping to mitigate the grid instability that has plagued parts of the country in recent years.

Cost concerns have led the governors of six states to petition the Biden Administration to do more to help the off-shore wind industry. The governors, including those of Connecticut, Massachusetts, New York and New Jersey, say that “without federal action, off-shore wind deployment in the US is at serious risk of stalling because states’ ratepayers may be unable to absorb these significant new costs alone”.

There are similar concerns about EU renewables targets with industry insiders calling on governments to do more to combat the rising cost environment and threat from Chinese companies. Other problems relate to difficulties with permitting, and the structuring of contracts where OEMs have historically absorbed cost increases during the development phase. The EU Net Zero Industry Act, the EU’s answer to the IRA, wants 40% of EU cleantech to be manufactured in the EU by 2030, but it is estimated that 80% of the €92 billion cost will have to come from private investors – something think tank Bruegel recently described as “not convincing”. It calls for an EU-wide funding policy that would avoid inter-state tensions around state aid, as well as reducing the burden on the private sector.

Windfarm challenges fall into three main categories:

- Technological: a poorly managed push for larger turbines has run into trouble with warranty claims driving losses and distracting OEMs from production activities

- Operational: badly structured planning processes as well as poorly structured commercial contracts are leading to project delays

- Economic: a dis-connect between the expectations of policy-makers that wind generation is “cheap” and the realities of rising supply chain costs and the adverse impact of higher inflation at the same time as cheap Chinese alternatives begin to take hold, particularly in Europe

All of these are combining to create significant headwinds for the industry. Unless they are addressed, renewables targets will remain a pipe dream.

Original article l KeyFacts Energy Industry Directory: Watt-Logic

KEYFACT Energy

KEYFACT Energy