Dave Waters

Director/Geoscience Consultant, Paetoro Consulting UK Ltd. Subsurface resource risk, estimation & planning.

Energy mood swings

There are some countries of the world that already get the drive for fossil fuel downshift. Sort of. They are not doing it perfectly, or altogether enthusiastically by any means, but they do – if begrudgingly at times – get a need for it. China, other East Asia, and Europe the front runners in “mindset development”. Not necessarily in doing it fulsomely – the picture is definitely a mixed bag with each region having talents and handicaps – but exploring how to. It’s probably no accident that these are also the two big economic powerhouse regions that do not have as much hydrocarbon resource of their own. They have lots of coal, but they know first hand the drawbacks of that and are examining how to wean. Again, with mixed results, but examining.

The US is more complicated (who knew) and conflicted. On one front taking all sorts of technologies forward, as usual, in the way we expect of it - but at the same time a superpower fundamentally based on a hydrocarbon economy. That's largely a domestically sourced one and given the foundation this has been for the US for so long, and still with significant resource left – it’s no surprise that the concept of weaning off hydrocarbons as a combustive fuel (as opposed to petrochemical use) meets with a more mixed reception. We can’t help observing that after all that has transpired, a country which at times (jury still out) looks like returning somebody like Trump as a presidential candidate, accordingly defies much prediction for the time being.

That said, what country can be predicted? India is another important unknown, as is Nigeria, Indonesia, Pakistan, Mexico, Brazil, and so on.

Hydrocarbon heft

There are three regions however, which strike me as hugely interesting and key to any pivot as the world changes how it does energy. They are Russia, Central Asia, the Middle East, and North Africa. The thing which sets these three regions apart is that state sponsored (or aligned) energy companies dominate energy production and distribution; they are huge exporters of energy to the rest of the world; and hydrocarbons have been the dominant factor in the 20th century in transforming these regions from being relatively poor, to becoming industrial and technological powerhouses.

To speak of them, to be clear, is not to speak of any one administration now – be it Putin, Arabian Emirs & Kings, or various autocrats of Central Asia and North Africa. It is to view them on much longer timescales – generational ones – as peoples and technological inheritances endowed with diverse resource. Whatever they look like now, what we can be sure of, is that 25 years, 50 years from now, they will look very different. How that difference manifests is a harder matter, but different, yes. One of the other key facets of these three regions is that not only are they hydrocarbon resource superpowers, but they are also renewables and mineral resource superpowers.

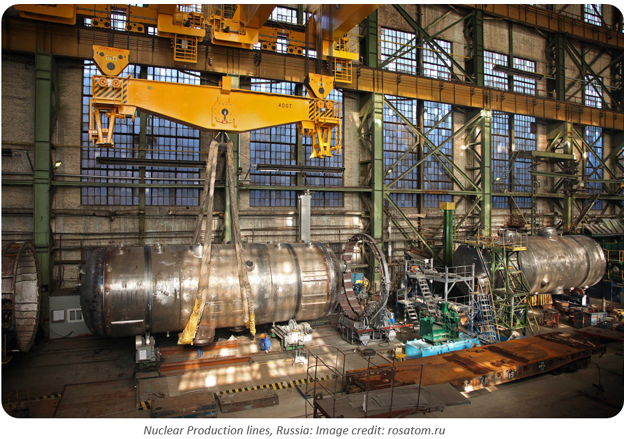

For Russia, we can also add the aspect of a nuclear technology superpower, and the global leader in export of big nuclear reactors. Not only that, but guess what, with Central Asia and the Middle East-North Africa regions being amongst the biggest export markets for that technology. Russia and its state “assisted” nuclear companies, including Rosatom, are properly progressing production-line style construction of new generation big reactors. For Russia, unlike many other big nuclear technology developers, virtually all of the raw material nuclear supply chains are safely domestic and enhanced by the resources of long-running allies.

Also, increasingly, Russia is developing the concept of nuclear “complexes” – with multiple reactors and reactor types, including fast neutron reactors which will help reprocess and reduce the amounts and half-life of any “waste” products that are not further reprocessible.

Still on that nuclear technology front, there is also “ostensibly” increasing agreement to co-operate with China. As ever though, an “it’s complicated” status attaches to any description of the Russia-China relationship and technology exchange. It has been so for a few centuries and is unlikely to change anytime soon.

Which renewable, which energy storage?

When we talk of renewable resources, it is an equally rich picking ground for these regions. We recognise solar for the Middle East, North Africa, and Central Asia, and hydroelectric and to an extent offshore wind for Russia. Onshore wind is a more mixed bag, but suffice to say North Africa, Arabia, Siberia and Central Asia were not dealt zero cards on that front.

A key question though – what routes for energy storage? Where solar is a dominant renewable resource, and fairly reliable during the day, the requirements for energy storage are shorter term, and relatively independent of season – the more so the lower the latitude. Where it is hydroelectric, or wind, the requirements are longer term and much more seasonally variant.

Short term options are ever expanding and include various flavours of battery and compressed and liquid air. Longer term storage is the harder nut to crack. Pumped hydro is the option of choice where you can find it - mindful of environmental and social impacts, and needing the funds to pay for it.

E-fuels of various kinds – so called “Power to X” routes, also raise their hand. Hydrogen, methanol, ammonia, e-kerosene etc. The e-fuel family are not efficient routes for energy storage, but where there is surplus that would not otherwise be used, they offer an improvement over throwing away. Their direct low-carbon competition is how much complementary sourcing of power from nuclear and other renewables can be transmitted long distance, to reduce the need for storage, replacing it with alternate give & take exchange of supply with other regions.

All these have financial costs of construction, environmental and social impacts, and the costs of efficiency loss – i.e. you lose some useable energy in the process of storing it. That as stated, matters less, if no-one is available within distribution distance to use it when it is available.

Momentum of making up minds

These technological questions are not however the biggest hurdle. The biggest obstacle is the mindset of wanting to change. Of picking a different event to run in for the energy Olympics. That is the really interesting dynamic.

When these huge petroleum and natural gas exporting regions get that they want to change – that is when the world will have reached a truly transformational watershed. I do not say so lightly when I say I believe they will. Don’t ask me when, but I believe they will.

That’s about long-term health over short term gratification. Something we can all relate to. When we recall the lift out of – if not widespread poverty – then very frugal lifestyles – that many of these countries have received by virtue of hydrocarbons, it is little wonder that a drive to shift away comes with hesitancy. Without encouraging delay, it is possible to empathise.

By the same token the scale of funds hydrocarbons have given these regions to reinvest in new energy approaches is unparalleled. They are already doing so from an R&D perspective, but for now much of it is of the “dabbling” variety.

The full decision to switch has not yet manifest. And let's be real - it's not looking imminent. But there are hints of a change of season... When we recognise that the countries of these three regions have about two thirds of the world's hydrocarbon resource – oil or gas – and probably ¾ if not more of the cheapest resource to access – we and they have pause to reflect. A reflection that they have an ultra long-running jewel box of petrochemical resource to craft, if they cease to see burning it as the best route to monetisation.

Front line of climate change ferocity

As a further accelerant, these regions are probably amongst the most vulnerable to emissions related climate impacts. The world’s climate is always changing but short of catastrophic events like bolide impacts and multi-millennia eruptive episodes, these tend to be slow. The issue we face is not how to halt climate change but how to limit its rate of change in a way that species and society can better adjust to. Urgently so, as these changes accelerate and accumulate in combined impact, often in unpredictable ways.

The Middle East and North Africa are among the regions most likely to bear the brunt of extreme heat events of a life-threatening magnitude and duration. Separately the air quality effects of combustion are already at crisis point in many of the Middle East, North Africa and Central Asia regions’ biggest cities and megacities. So, as it has been in China, and will increasingly be in India, these domestic crises will be an ever-growing domestic incentive for combustion reduction. Whoever is in charge there.

In Russia the effects are at the other end of the latitude scale. It is possible to fancifully imagine that warming will have its attractions, but the threats loom large to the country with the greatest absolute temperature changes. Threats to vast tracts of cool temperate and sub-arctic forest & scrub & tundra through drought and fire, and the implications for permafrost loss, including accelerating releases of swamp methane and weathered/leached minerals. Much Siberian infrastructure is vulnerable to ground stability changes with loss of permafrost. Not least pipelines.

The increased exposure to flash floods and droughts in regions now mostly sourced from alpine snow & ice reservoirs will be important not just in Russia but in Central Asia. These are all countries whose people have a well-deserved reputation for being tough and resilient, but these effects are likely to be on an unprecedented scale with key implications for food production and water resource.

Energy muscle

Russian policy on such things now is of course typically opaque and cloaked in multiple shades of ambiguity as always – but Russia has always been more pluralistic on a scientific and industrial front than it has been on a political one. There are signs it is awakening to the issue through the efforts of its own scientists and as a result of increasingly severe domestic events. It won’t be pushed, but before long it might be doing much of the pulling.

Perhaps for now Russia sees any “transition” as a growth of nuclear more than renewables expansion, given the Russian legacy and love of “muscular” industrially forged energy. Rosatom’s CEO recent discussion of 25% of Russian energy coming from nuclear by 2045 seems to hint at this (https://www.neimagazine.com/news/newsrosatoms-development-plans-8592063/).

This is of course what the CEO of any nuclear company would be likely to say, and Russian ones are no different – but to say so in today’s Russia is suggestion at least that the nation is increasingly alert to the subject, whatever we think of the approach. After all, “Mr. Putin defended a dissertation in economics and subsequently published an article outlining his view of the appropriate role of the Russian state, and of vertically integrated financial-industrial groups, in the mineral resource sector, and particularly in the oil and gas industry” - (Balzer, 2005). The administration is no stranger to all things energy.

The most interesting dynamic may well be growing interdependence and pragmatism between China and Russia superimposed on the longstanding rivalries, disputes and suspicions. China’s increasing preference for renewable routes over nuclear ones (without halting either) perhaps eventually gaining ground in Russia too. Both countries equally mindful that the histories of the other are prone to swift and often unpredictable changes. The policy in both, much more dependent than most countries of comparable size, on the fortunes and misfortunes of individual leaders.

No small undertaking, but once undertaken…

For Russia, Iran, Iraq, Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, UAE, Algeria, Libya, Kazakhstan, Azerbaijan, Egypt, Qatar, Turkmenistan, et al., to change their approach to hydrocarbons is no small ask. It is not the external ask that will matter, but the internal, domestically sourced ask. Yet it is hard to see that question not being posed more and more. How quickly probably depends on the rate at which domestic weather, air quality, algal bloom & other biological "plague", events impact populations and infrastructure. Also on how quickly the rest of the world – their customers - changes around them, and with it their source of income.

Whatever energy-transition waves come all our way, these regions will want their own surfboards. They haven’t got their wet-suits on yet, but the day they decide to fit one for size is the day something profound will have changed.

The bad news/good news element of the story is the more autocratic nature of many of the administrations in these countries. Given this and the embedded links to major state-run or aligned energy corporations, once the change in direction is selected, short of a major change in geopolitics, things probably won’t hang around.

Reference

Balzer, H. (2005). The Putin Thesis and Russian Energy Policy. Post-Soviet Affairs, 21(3), 210–225. https://doi.org/10.2747/1060-586X.21.3.210

KEYFACT Energy

KEYFACT Energy