On 27 August 2025, Mitsubishi Corporation issued a statement announcing its withdrawal from three offshore wind projects in Japan. The projects, totalling 1.7GW, were originally awarded in Japan’s Round 1 auctions in 2021 to Mitsubishi-led consortiums, with target commissioning dates in 2028 and 2030.

While the withdrawals have a significant impact on Japan’s near-term 2030 targets, the country’s longer-term outlook remains encouraging. If the government takes this opportunity to reassess what went wrong and swiftly re-tenders the Round 1 projects as planned, the long-term pipeline can remain robust. This is especially true looking further ahead, 10 to 15 years from now, where Japan is well positioned to leverage its vast floating wind potential, reinforced by recent policy momentum.

2030 national targets at risk

Mitsubishi’s exit from the Noshiro-Mitane-Oga (479MW), Choshi City (390MW) and Yurihonjo (819MW) projects located off the coasts of Akita and Chiba prefectures, puts Japan’s 2030 offshore wind targets at risk.

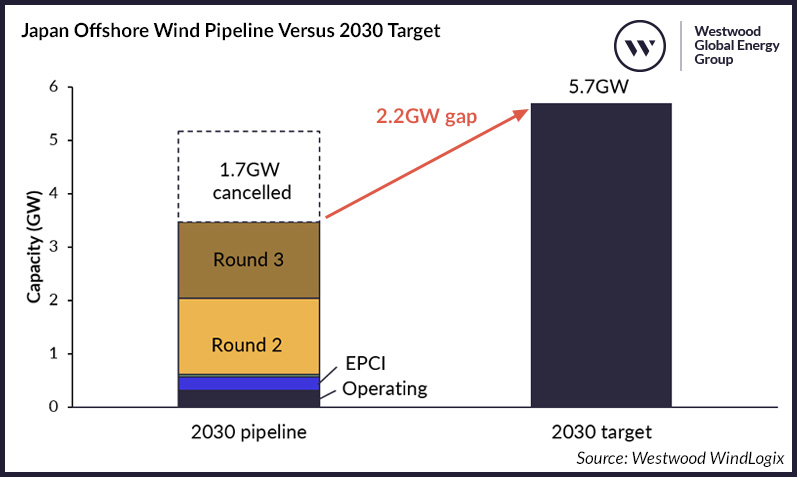

Including operational capacity, projects under construction, and awards from the Round 2 and 3 auctions, the gap between the current pipeline and Japan’s 5.7GW target has now widened to 2.2GW (or 38% of the total target).

Figure 1: Japan Offshore Wind Pipeline Versus 2030 Target

Source: Westwood WindLogix

Even if new tenders are issued this year, targeting commissioning by 2030 would leave a tight project development window of only five years. In comparison, commercial projects in established offshore wind markets such as the UK and Germany have typically taken between seven and 10 years from lease award to commercial operation date (COD). In Japan, the 112MW Ishikari Bay Port project took five years to achieve COD after receiving a feed-in tariff (FIT) agreement in 2019 at JPY36/kWh (US$0.24/kWh); with larger project sizes involved in Round 1, longer construction periods would be expected.

Why did Mitsubishi exit?

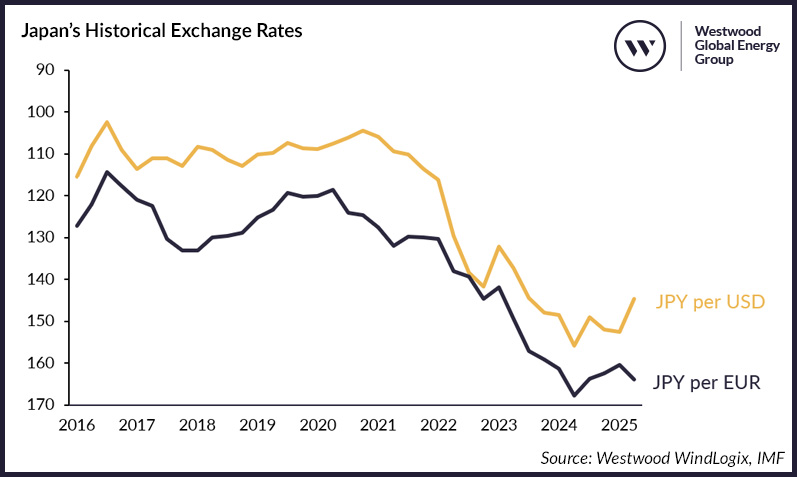

The Mitsubishi-led consortiums placed low FIT bids of JPY11.99 to 16.49/kWh (US$0.08-0.11/kWh) in 2021, which proved financially unviable amid rising costs, weakening exchange rates and supply chain constraints.

Figure 2: Japan’s Historical Exchange Rates

Source: Westwood WindLogix, IMF

In February 2025, Mitsubishi announced it would re-assess its business plans for the three projects. The government offered to retrospectively transition Round 1 projects from the FIT scheme to a feed-in premium (FIP), however this proved insufficient to support project viability. The Mitsubishi consortia ultimately withdrew, forfeiting JPY20 billion (US$136 million) in deposits.

Understanding what went wrong

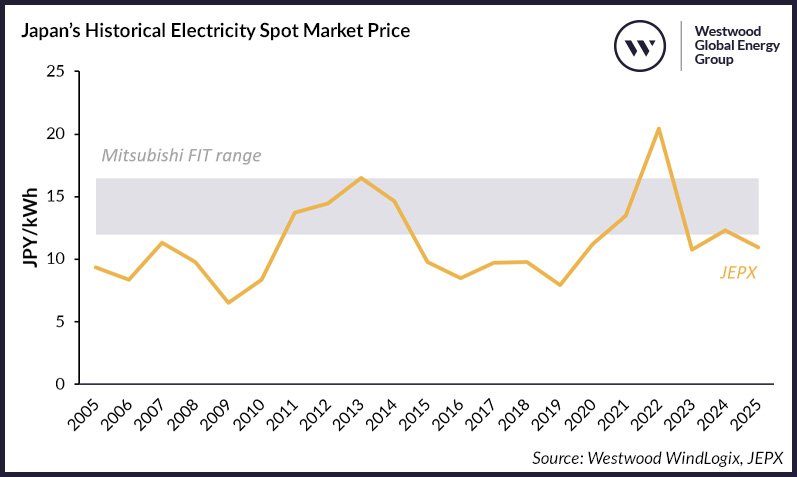

While specific FIP details for Round 1 were not publicly announced, several projects from Rounds 2 and 3 had taken an FIP price of JPY3/kWh (US$0.02/kWh), known as the “zero-premium” level. Premiums are paid by the government based on the difference between the FIP rate and the “reference price”, which is set based on wholesale prices. With such low FIP rates, it is unlikely that premiums would be paid and therefore a project would need to rely on other revenue sources such as the wholesale market or power purchase agreements (PPAs).

Developers under FIP could sell to the Japan Electric Power Exchange (JEPX), where average annual electricity spot prices have trended between JPY10.74 and 20.41/kWh in the past five years. However, this may have been insufficient for Mitsubishi, given market volatility and with historical prices not trending significantly higher than Mitsubishi’s original FIT bids, especially since Mitsubishi claimed that construction costs had “more than doubled”.

Figure 3: Japan’s Historical Electricity Spot Market Price

Source: Westwood WindLogix, JEPX

Alternatively, projects under FIP could also seek corporate PPA (CPPA) off-takers. However, securing corporate off-takers – particularly off-takers willing to pay premium prices for offshore wind – would also have posed a challenge for Mitsubishi given the limited CPPA market and competition from other Round 2 and 3 developers that had a head start in securing buyers.

Another possible contributing factor was that Mitsubishi had planned to use GE Haliade-X turbines instead of the more widely adopted Vestas or Siemens Gamesa models. GE has since scaled back on its turbine business, and recent incidents, such as the removal of Haliade-X turbines from Vineyard Wind 1 in the US due to manufacturing faults, could have introduced further uncertainty for Mitsubishi.

What’s next for Japan’s offshore wind?

The government has stated that it plans to re-auction the three sites, although it remains undecided if the sites will be reauctioned first or if Japan will proceed with its fourth auction, previously targeted to launch as early as autumn 2025.

Given the situation, Japan’s 2030 targets are likely to be missed – however, this short-term setback may not necessarily reflect the outlook for future rounds. It presents an opportunity for the government to use Round 1 as a learning experience, reassess its approach, and refocus efforts on supporting future auctions, including Rounds 2 and 3. This is especially critical since many projects won under zero-premium bids and will likely face similar cost issues. Improving the wider business environment and bidding system will be key to the success of future projects.

Encouragingly, the government is already reviewing the causes of Mitsubishi’s withdrawal and aiming for a swift re-tender. Port development is underway in Akita, offering a positive note for prospective future bidders. Mitsubishi has also stated it would provide data to support a smooth transfer when the projects are re-tendered.

Despite the current setback, Japan’s long-term offshore wind potential remains unchanged, especially with the added prospect of floating wind. Furthermore, even if 2030 targets are not met, it will still be a significant achievement should Japan be able to bring its 3.5GW capacity pipeline to commercial operation, given that operational capacity currently stands at 308MW.

Hui Min Foong, Senior Analyst – Offshore Wind

hmfoong@westwoodenergy.com

Original article l KeyFacts Energy Industry Directory: Westwood Global Energy

KEYFACT Energy

KEYFACT Energy